We’ve heard it before and we’ll hear it again because it’s a truth. We can’t do it all and sometimes we just need to say No.

We’ve heard it before and we’ll hear it again because it’s a truth. We can’t do it all and sometimes we just need to say No.

I was reminded of this when a writer friend sent a link to this blog and the last line of what Seth Godin says is “No is the foundation that we can build our yes on.” I think that’s brilliant.

And a reminder I obviously need tattooed on my forehead. No matter how many times I remember this, it’s usually after I’ve over committed myself – again – and I’m stressed out about having too much to do. Like right now.

We all have families, friends, organizations, careers, and so on that we need to do things for on the occasion. The trick is balancing it, prioritizing it, and keeping what’s important always in mind. And sadly, sometimes that means we just can’t do it all and stay sane. I know I feel crazy more often than I should.

For me, it’s a circular snowball effect. Let me explain the cycle: I feel good, so I say Yes to too many things. When I don’t have enough time to get all of said commitments done, I start to stress. Stress impacts my depression. My depression makes it harder to be productive for even the important stuff so now everything is harder. I realize I’m a dope and try to wrap up or shed the commitments I can as soon as possible so I can focus on the ones that are super important. I push through and say No to a lot of things. Commitments ease up so I can be productive where I need. I feel better. I feel good….. and it begins again. Hence the tattooed reminder.

The friend who sent out the link was one of the people I asked to guest blog for this month. When I did a follow-up to see if she was going to or not, she said, “You know, at this point, I’m going to have to say no. Does that screw you over? I don’t want to screw you over.” And I thought, Smart Woman! I told her I completely understood. And I do.

It isn’t even just the special projects we should be saying No to… like the class I’m teaching that I haven’t written yet, or the motorcycle riding class I’m taking over four days, or the offer to help an elderly friend run errands. It’s the daily grind stuff that keeps my calendar looking like a multi-headed hydra on steroids has planned a host of events for each damn head for each damn day of the week. Ridiculous. And I have no one to blame but myself!

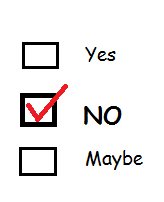

Who else is suffering from the dreaded Yes-itis Over-committus disease? Raise your hands. Now commit with me to this instead – I will say No. Repeat it with me, now. I WILL SAY NO.

When asked to XXX, I will say No.

We can find a cure together, people. I believe this. 🙂

I read a book recently, “18 Minutes: Find Your Focus, Master Distraction, and Get the Right Things Done” by Peter Bregman. One of the things he says to do is come up with a list of the five most important goals for your year, like spend time with family, focus on career, and so forth. And then whenever a request is made, assess whether that request falls squarely inside one of your target goals or whether it is a distraction away from it. Say yes or no accordingly.

I’m trying to do that…. And as I say ‘try’ I hear Yoda in the back of my brain, saying, “Try not. Do, or do not.”

I know what I need to do.