I’m old enough to remember the days before my household got a VCR. If we wanted to watch a movie, we had to catch it at our local cinema. If we wanted to watch a TV show, we had to make sure we were sitting in front of the TV when the show came on. If we were busy, or sick, or just forgot, our chance to see it was gone.

But what I remember most was the bittersweet knowledge that when I was watching a movie I loved, I wouldn’t be able to just watch it again any time I wanted. Until–if–it aired again, I would have to content myself with my memories…

…and my books.

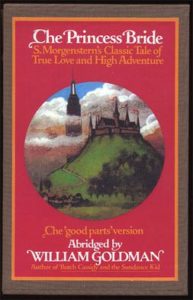

I had junior novelizations of films, illustrated with pictures of stills from the movie. I had movie tie-in novels, designed to recreate the story as best they could using the printed word instead of audio and visuals. I even had comic-book adaptations. Later, when we got our VCR, I had the experience of renting movies that I’d previously known only as books…this was particularly amusing with movies like Star Trek: The Motion Picture and Back to the Future, which had begun as movies, but which I’d first experienced as books.

Many movies and shows are based on books, but sometimes it’s the other way around. Tie-in books are created to tell the story of a movie (or video game, or TV show) in another format.

What’s the purpose of a tie-in book, though, in an era where fans of the movie are going to be able to download it on their computers, stream it on Netflix, or buy it on Blu-Ray? Now that it’s easy to get a movie and watch it any time you like, what’s the point of having a novel version?

Novels are a different medium from movies, TV, or games, and the best tie-in novels play to the strength of the medium. In a novel, it’s easy to write about what a particular character is thinking, or give the reasons why a character made a certain choice. In a movie, it’s a lot harder to do this without resorting to the voice-over narrative technique, a technique which needs to be used appropriately and sparingly. Tie-in novels can provide new insights into why characters do what they do, and how they feel about the events that are unfolding.

Tie in novels can also provide looks “behind the scenes.” Maybe certain scenes were cut from the finished movie. Maybe the movie didn’t make it clear if a certain character survived or not…but the book does. Maybe a plot hole’s been patched. Maybe we get to find out more about the villains, or the minor characters, or a group who were “out of the spotlight” while the original movie focused on the protagonist.

(For the record, “Snakes on a Plane” makes a much better book than a movie. The novelization is a much more character-driven, much meatier, much more entertaining story. And the cat lives.)

How do you write a bad tie-in novel? Create a generic story of the same genre and slap on the names of the characters from the show. Fans will not be happy if the characters that they know and love are acting jarringly out-of-character, missing their unique defining traits, or seem to be oblivious to information that’s common knowledge about their world in their original medium. The tie-in needs to feel like “part of” the world it claims to represent.

Most importantly, these days, tie-in novels aren’t bound to retelling the story of a video game/movie/TV show. Many tie-ins are prequels or sequels to the action depicted in the video game or movie. Others “fill in the gaps” between the second and third games in a series, or the second and third movies in a franchise. Particularly with video games, tie-in novels can flesh out the world of the games, provide backstory, and give deeper insights into the characters.

In the age of Netflix, the art of the tie-in novel isn’t in re-hashing someone else’s script; it’s in expanding that script’s story, providing details and scenes and character depth that enhance the experience of re-watching the original.