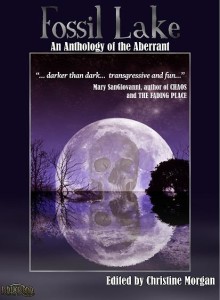

I gave a copy of Fossil Lake: An Anthology of the Aberrant to my parents with a proviso attached: it’s not autobiographical.

The assumption would be easy enough to make. My contribution to Fossil Lake, the short story “Mishipishu: The Ghost Story of Penny Jaye Prufrock,” is set at a summer camp for kids. The name of the camp in the story, Camp Zaagaigan (the Algonquin word for “lake”) is fictional; so is Lake Mishipishu (I actually checked on the maps and found a Mishibishu Lake…) My parents, however, would be able to name the real camp and the real lake after they read the story: from the cabin line to that infamous H-dock, the layout of Camp Zaagaigan mirrors its real-world counterpart, and they drove me there often enough to recognize it.

The assumption would be easy enough to make. My contribution to Fossil Lake, the short story “Mishipishu: The Ghost Story of Penny Jaye Prufrock,” is set at a summer camp for kids. The name of the camp in the story, Camp Zaagaigan (the Algonquin word for “lake”) is fictional; so is Lake Mishipishu (I actually checked on the maps and found a Mishibishu Lake…) My parents, however, would be able to name the real camp and the real lake after they read the story: from the cabin line to that infamous H-dock, the layout of Camp Zaagaigan mirrors its real-world counterpart, and they drove me there often enough to recognize it.

From there it’s just one step further to wondering how much more of the story is real.

I’m often asked whether the characters in my story are “me,” or whether the events are “real,” and all I can ever say is that I write semi-true stories. Semi-true in that I’ve never been able to take a person, event, or revelation and transcribe it into fiction word-for-word. As a writer friend of mine says, real life doesn’t have to make sense, but fiction does. Even if I’m starting with something “inspired by a true story,” in order to make event or character coherent, I have to add things here, or take things away that might have happened in real life, but don’t add anything useful to the tale I’m telling. Sometimes changes to the story make it more dramatic, more compelling, or more satisfying; and so the events “inspired by a true story” move ever farther away from a faithful reflection of reality. After all, I’m writing fiction—I’m not required to report on reality. I’m required to tell an engaging and powerful tale.

And semi-true in that I do my best to write characters who feel real: who behave in realistic ways, who are recognizable and relatable, who are emotionally honest. When I write them, I put myself in their position and see the world through their eyes; and yes, to an extent, I feel what they feel, and try to express that emotion in the words I’m writing. Often this emotional connection is informed by my own real-world experiences. I do know what being bullied feels like. I do know what doing something I know is against the rules feels like. I don’t know what it feels like to drown, but I do know what it feels like to not be able to breathe, so I write about that…and imagine one step farther, based on research and my own ideas. These characters aren’t me, but they have pieces of my emotions inside them.

So no, I was never bullied at that summer camp you sent me to, Mom and Dad. No, I never snuck out of the cabin after hours. No, I was never a suicidal twelve-year-old, and no, I’ve never lost sight of the line between reality and imagination.

…or at least, I’ve always found it again in time.

About Mary:

Evan Braun is an author and editor who has been writing books for more than ten years. He is the author of The Watchers Chronicle, whose third volume, The Law of Radiance, was released earlier this year. In addition to specializing in both hard and soft science fiction, he is the managing editor of The Niverville Citizen. He lives in Niverville, Manitoba.

Evan Braun is an author and editor who has been writing books for more than ten years. He is the author of The Watchers Chronicle, whose third volume, The Law of Radiance, was released earlier this year. In addition to specializing in both hard and soft science fiction, he is the managing editor of The Niverville Citizen. He lives in Niverville, Manitoba.