Guest Post by Nicole Cushing

First things first: let’s acknowledge the elephant in the room. Extreme horror fiction hasn’t always enjoyed the best reputation. Despite the commercial success of books like Bret Easton Ellis’ American Psycho and Jack Ketchum’s The Girl Next Door, the field is often seen as only catering to a niche audience. Despite a pedigree that arguably extends at least as far back as early nineteenth century Polish author Jan Potocki, the field is often seen as a playground for recent generations of subliterate hacks.

Perhaps that’s why so little has been said about how to write extreme horror fiction skillfully: so many people seem to assume that such fiction requires little skill to write.

to assume that such fiction requires little skill to write.

And yet my experience is that extreme horror does require skill. As an extreme horror author, you’re handling dynamite. And, for all sorts of reasons, dynamite shouldn’t be used by untrained hands.

Ironically, my interest in writing extreme horror fiction may have started in the least likely of places: my college creative writing class. I was introduced to Natalie Goldberg’s book Writing Down the Bones: Freeing the Writer Within. “Go for the jugular,” Goldberg advised at one point (the italics hers). She went on to clarify what she meant: “(If something comes up in your writing that is scary or naked, dive right into it. It probably has lots of energy.)”

Now, obviously when Goldberg used words like “scary” and “naked”, she was using them to convey the importance of a writer tapping into their own emotional rawness and vulnerability. Of course, she wasn’t advocating literally writing about scary people or naked people. She probably wanted her readers to feel emboldened to write about difficult but relatively genteel topics (such as when their grandmothers died of old age). She probably wouldn’t be overjoyed to learn that I found her advice helpful in the writing of a novel with graphic depictions of murder and rape.

And yet, I’d argue that her advice isn’t necessarily at odds with the writing of extreme horror fiction. Graphic violence doesn’t exist in an emotional vacuum. Graphic sex doesn’t exist in an emotional vacuum. Graphic sexual violence certainly doesn’t exist in an emotional vacuum. Trauma, in general, doesn’t exist in an emotional vacuum.

To the contrary, all of these experiences have (to borrow Goldberg’s phrase) “lots of energy”. And that energy can be used to emotionally move the reader in a way no other variety of fiction can (particularly if an author is willing to use their own experiences with grief, depression, or trauma in their work). Bringing that sort of vulnerability to writing horror fiction is what Jack Ketchum has called “writing from the wound”.

Which brings me to the advice I have to share today for writing extreme horror fiction (which, actually, applies to any type of fiction): a depiction of violence is only as powerful as the emotional context the author weaves around it.

What do I mean by this?

Indulge me in a little thought experiment. Imagine you’re walking along the sidewalk in your town or city, and (out of nowhere) an unrecognizable fellow-pedestrian slaps you hard on the face and then runs away. When you look up to see where they went, you realize they’ve slipped around a corner and can no longer be found.

Imagine the emotions that would be bouncing around your head in such a situation. The intrusion of random violence into your day (and the assailant’s subsequent flight) would likely leave you confused. You might, in such a situation, ask yourself: “Who was that?” (Or even, “Did that really just happen?”)

But you’d also feel a stinging pain in your cheek that would provide assurance that it did really happen.

And maybe other pedestrians would notice the incident and stare at you. This could lead you to feel self-conscious. Maybe even embarrassed. It makes no logical sense for you to feel embarrassed under such circumstances. You didn’t do anything wrong. But being singled out for attention in a public place creates, at the very least, tension.

So in this scenario, you’d be confused. In pain. Possibly embarrassed, definitely tense. And all of these emotions would likely lead to yet another emotion, anger. Maybe you’d want to slap your assailant back (or up the ante and totally clobber them). Depending on what else is going on in your life, you might count this incident as the most troubling event of your year.

I could go on and on about the emotional response to a single slap, but there’s no need to. The point is: even relatively mild violence carries a wide array of emotional consequences that can make an impact on the reader, if a writer can effectively convey them. Therefore, a depiction of extreme violence carries an even greater burden. It must be emotionally honest in a context where the emotions are heightened to their highest state.

And yet, this doesn’t mean an extreme horror writer can just resort to having characters scream their heads off. (Indeed, many of us have seen how so-called “scream queens” are often used for over-the-top comedic effect in horror films, deflating any sense of true suspense or terror.)

Mere screaming will not suffice. There must be groaning, wailing, whimpering, hyperventilating, and sobbing as well. The full range of fear and sorrow must be depicted. This is the difference between a cheesy scream queen flick and a truly disturbing piece of cinema like Wes Craven’s original Last House on the Left (which, despite its status as an exploitation film, accidentally managed to hit audiences someplace deeper through relatively realistic performances which captured the emotional texture of trauma).

That (in my opinion) is the mission of extreme horror fiction: to capture the emotional texture of trauma and related experiences.

Extreme horror looks trauma in the eye, without blinking. It doesn’t sensationalize the violence by making the villain an evil genius with a quirky m.o. It doesn’t trivialize the violence by churning out a body count so high that an odd sort of repetitive, predictable casualness settles in. It allows each slap, each punch, and…yes…each wound its natural emotional consequence. See the aforementioned Ketchum novel The Girl Next Door for an example of this style of horror at its finest.

This sort of writing isn’t for everybody. It might be best to think of it as a calling. There are more than the usual amount of hardships you endure in this career path. Writing extreme horror can take an emotional toll on the author in a way other subgenres don’t. Agents and editors in New York generally turn their noses up at extreme stuff, so you’re often limited to the small press. Strangers may completely misunderstand you, and think you condone the hideous things you write about.

But, if this path is right for you, none of that will matter. What will matter is that you’re telling the truth about how the world (at its absolute worst) really works. And that is a noble career.

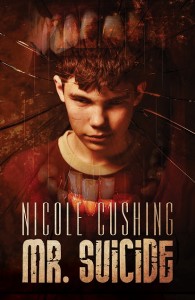

About the Author:

Shirley Jackson Award finalist Nicole Cushing is the author of the novel Mr. Suicide, the short story collection The  Mirrors, and multiple stand-alone novellas.

Mirrors, and multiple stand-alone novellas.

She has garnered praise from various sources, including Thomas Ligotti, John Skipp, S.T. Joshi, Jack Ketchum, Poppy Z. Brite, and Ray Garton.

About the Book:

How many times in your life have you wanted to slap someone? Really, literally strike them? You can’t even begin to count the times. Hundreds. Thousands. You’re not exaggerating. You’re not engaging in… whatchamacallit? Hyperbole? You’re not engaging in hyperbole.Maybe the impulse flashed through your brain for only a moment, like lightning, when someone tried to skip ahead of you in line at the cafeteria. Hell, at more than one point in your life you’ve wanted to kill someone; really, literally kill someone. That’s not just an expression. Not hyperbole. Then it was gone and replaced by the civilized thought: You can’t do that. Not out in public.But you’ve had the thought…