A guest post by Joshua David Bennett.

In fifth grade, I wrote my very first story about a raccoon space pirate named Bucky. Way before Guardians of the Galaxy, Bucky was breaking new ground for raccoons, flying through space in his minivan with his best friend Raven, looking for treasure.

In fifth grade, I wrote my very first story about a raccoon space pirate named Bucky. Way before Guardians of the Galaxy, Bucky was breaking new ground for raccoons, flying through space in his minivan with his best friend Raven, looking for treasure.

I was trying to recreate the wonder I had when I first saw Star Wars or read Hitchhiker’s guide.

For better or worse that story is lost to the ages. But thirty odd years later, I still love the thrill of exploring a universe in my own mind.

This month on Fictorians we’re talking tools, with a focus this week on worldbuilding. We won’t be going deep on principles or philosophies in this article. For that, Writing Excuses has worldbuilding episodes that are relevant whether you are designing a magic system, mapping nebulae, or even trying to fill historical gaps in 19th century Paris. Perhaps the best advice from them is to stretch beyond your story’s core characters and conflicts to include everyday details. If you can show how magic and science have affected even the ordinary, your world will be much richer.

The tools below can help. There will be many. Grab a coffee and make sure your browser can handle twenty tabs at once.

Starting Big

Assuming I already have a character and a conflict, my process always begins with setting. Yours may start elsewhere. I need evocative scenery for the characters to play in, and what scenery is grander than the final frontier?

If you’re writing a science fiction, the tools below can help you populate your vast universe with solar systems for your characters to explore. For fantasy, these tools can provide the scientific backing for far stranger worlds than Tolkien imagined.

Universe Sandbox ($10) is a beautiful space simulation program. You can spin the Earth around the Sun at 10x time, restore Pluto’s pride by scaling it into a megaplanet, or add brand new worlds to our system. The upcoming sequel adds even more options, like procedural planet creation, terraforming, and planetary collisions.

StarGen is a free online tool with no graphical flair to speak of, but makes up for it with scientific rigor. Give it a few parameters and it creates a whole solar system of planets, each complete with data on surface temperature, atmospheric mix, length of year, and a dozen other things you might need to know.

For an actual image of your world, turn to Fractal Terrains ($40, Win) or the free Fractal World Generator. Either will generate a random world, but Fractal Terrains will also let you edit coastlines, mountains and islands to your liking. Tweak humidity levels and heat to see different terrains appear. Then let the program apply wind and water erosion, and pretty soon you have riverbeds running through your landscape.

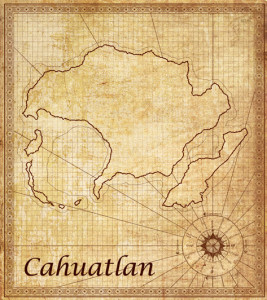

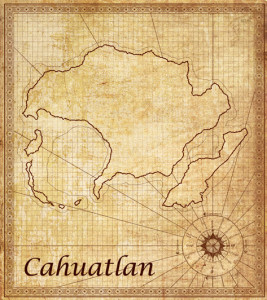

Mapping

A good map is a wonderful writing aid. I use mine for story consistency, travel times, and to see which key locations haven’t yet been used in a scene. For a reference map, the only tools you really need to are pen, paper, and inspiration. For inspiration, I highly recommend the Cartographer’s Guild. Here you’ll find amazing fictional maps that can give you ideas for what kinds of details to include on your own.

locations haven’t yet been used in a scene. For a reference map, the only tools you really need to are pen, paper, and inspiration. For inspiration, I highly recommend the Cartographer’s Guild. Here you’ll find amazing fictional maps that can give you ideas for what kinds of details to include on your own.

If you want a more advanced tool, there are several. Campaign Cartographer ($45, Win) and Fractal Mapper 8 ($35, Win) are both fantasy mapping tools for the gaming crowd. Draw out continents and then use the available symbols to add forests and cities. Fractal Mapper goes a step farther and allows you to map building interiors as well.

Gimp and Inkscape are fully featured and fully free graphic programs. The learning curve is steep, but either can create maps, mock up covers, house sigils or anything else you can imagine.

But perhaps the easiest way to get a detailed look at your world is to let a game make it for you. Games like Dawn of Discovery ($10, Win) and Anno 2070 ($30, Win) simulate building and managing a city, in Renaissance Europe and the near future respectively.

Filling your world – Order, Chaos and a little help from friends

Unless your story is dystopian, you’ll want to fill those empty maps with life. This can be an enormous task, and it can be hard to know where to start. Fortunately, the fantastic and amazing Kitty Chandler has put together the WorldBuilding Leviathan and the equally amazing Belinda Crawford has created a Scrivener template out of it. In either form, the Leviathan prompts you with questions about your world’s timeline, culture, technology level, economy, biases, taboos, factions, and a dozen other variables. In the end, you’ll feel as if you’d actually lived there.

Sometimes the ideas won’t come, and trying to brainstorm will send you into a glassy eyed stupor. When that happens, introduce some chaos to get yourself unstuck. Seventh Sanctum has a trove of random generators for anything from currency (two Imperial credits) to dragon breeds (Persian Rockstrike), to diseases (the Gray Sneeze) and more. If you’re lacking for a detail to get you out of a rut, this can be just the ticket.

Other times, the ideas come freely, but leave you with more questions than answers. The Worldbuilding Stackexchange is a great place to get general help. When I last checked, the top question was “How to create a nuclear explosion localized to only a few square feet.” We’ve all wondered that. Now you can find the answer.

If your questions are specifically about the creatures you’re putting in your world, the Speculative Evolution forum might be more your speed.

Or, if you are developing your own magic system, Brandon Sanderson’s fansite hosts a Creator’s Corner with people doing the very same thing.

Building a Story Bible

Pretty soon, you’re going to need a story bible to hold all the details about your world. Scrivener ($40) is fantastic not just for writing but also for brainstorming and storing every snippet about your world.

Pretty soon, you’re going to need a story bible to hold all the details about your world. Scrivener ($40) is fantastic not just for writing but also for brainstorming and storing every snippet about your world.

Personal wikis are another popular option. These act as your world’s Wikipedia, with easy linking between your various topics. You can quickly build a network of articles, complete with tables or inline images. WikidPad is a favorite tool of folks over at Writing Excuses, but I’ve found TiddlyWiki or ZimWiki to be more intuitive. All three are free to use. Whatever your preference, these tools can help you to build a great reference tool for your world.

Conclusion

As enticing as these tools can be, Know When to Stop. Worldbuilding should not be an exercise in filling endless binders with your own private sandbox. Instead, it should always serve to enhance the story. I love the way my friend James Artimus Owen puts it. “We have the best job. We get to create things in our minds that are so amazing, other people are going to pay to know what they are.”

Make sure these tools drive you back to the open page, and to finishing the story so you can share it with others.

Author

Joshua David Bennett is a scotch lover, history enthusiast, graphic artist, and world traveler. His first novel, Seacaster, is a Caribbean-Aztec fantasy that tells the story of a young man at war with the magic coursing through his veins. Joshua lives in Colorado with his wife and son.

Gregory D. Little is the author of the Unwilling Souls, Mutagen

Gregory D. Little is the author of the Unwilling Souls, Mutagen