A guest post by Brenda Sawatzky

“I never get mad, Miss Threadgoode, never. The way I was raised, it was bad manners. Well, I got mad and it felt great! I felt like I could just beat the shit out of all those punks. Excuse my language. And then, when I finish with those punks, I’ll take on all the wife-beaters like Frank Bennett. Machine gun their genitals. Towanda will go on a rampage. I’ll slip tiny bombs into Penthouse and Playboys so they explode when you open them. I’ll ban all fashion models who weigh under 130 pounds. And I’ll give half the military budget to people over sixty-five and declare wrinkles sexually desirable.”

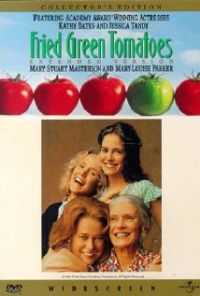

Every one of us could name an all-time favorite movie. They move us, uplift us, make us laugh and sometimes cry. They resonate with us long after the closing credits roll, finding a nesting spot deep within us from which they’ll surface from time to time to bring a smile to our faces. For me, the movie was the 1991 dramedy Fried Green Tomatoes. With award-winning actresses such as Jessica Tandy, Kathy Bates, Mary-Louise Parker, and Mary Stuart Masterson, the stage was set for a parallel story about women, friendship, and finding strength and solidarity in a man’s world.

As writers, we know the importance of storyline, plot, and setting. But in my opinion, a great story is character-driven. Movies and books can take on a variety of milieus, drop us into different time periods, and deliver us to places we’ve never been before, but the characters are what stay with us long after we’ve turned the closing page or returned the TV set to its primordial state of blackness. When we can connect and find symbiosis with a character, we are drawn into their life, regardless of where they live, their age, or what they look like.

In Fried Green Tomatoes, we are introduced to Evelyn, a timid, middle-aged housewife desperate to save her vapid marriage from complete stagnation. A fortuitous friendship develops with Ninny, a soft-spoken, lonely woman in a nursing home who regales Evelyn with stories from her past, giving Evelyn a reason to return time and again, the story developing with each visit. Evelyn has made numerous failed attempts at restoring the sexual fire in her marriage-dieting, wrapping herself in cellophane (you have to see the movie), and attending a class where she’s encouraged to explore her female sexuality.

Ninny: Now you tell me what’s botherin’ you, sugar.

Evelyn: I just feel so useless. So powerless.

Ninny: Everybody goes through that, but you can’t stop eatin’.

Evelyn: Every day I try and every day I go off. I hide candy bars all over the house.

Ninny: A candy bar ain’t gonna hurt you none.

Evelyn: Oh, no. But ten or eleven? (sigh) I can’t even look at my own vagina.

Ninny: Well now, I can’t help you on that one.

Evelyn eventually discovers self-empowerment by making a connection, vicariously, to an obstinate character in Ninny’s story-Idgy Threadgoode. The movie jumps from Evelyn and Ninny’s 1980s suburbia to a tumultuous 1930s Alabama, linked by Ninny’s story. Ninny, oftentimes in narrative format, draws us into the lives of two young friends, Idgy and Ruth, brought together by chance and inexplicably connected by the powerful love that develops between them.

The movie’s characters are deep yet vulnerable, sucking the viewer into every fragment of their topsy-turvy lives until we and they are intrinsically joined.

As writers, this is our challenge: to create characters that share a humanity with our readers, that demand the reader’s loyalty and make them desire to develop a relationship with them. In part, Fried Green Tomatoes does that by cloaking each character in an attribute or idiosyncrasy that is unique to them, characteristics that we can identify with. Ninny is witty and kind, Evelyn insecure and self-depracating. Ruth is innocent and trusting to a fault while Idgy has developed a thick skin of self-preservation, keeping the world at arm’s length. When thrown together in one story, these characters build on each other’s strengths and break down impenetrable walls. They allow us to believe that anything is possible with a good friend at your side.

The movie also dabbles heavily in the “stuff of life,” the experiences that are the great equalizers of humankind. Idgy’s heart breaks over the death of a brother, and then a best friend. Ninny reconciles herself with aging and mortality. Ruth finds strength in the face of marital abuse, single parenting, and oppressive religious dogma. And Evelyn, of course, finds her spirit, previously lost in disappointing relationships. These, too, are the things that connect us to characters and make us rally around them.

Finally, for me, a memorable movie or book will always include great quotes, little truths surreptitiously wrapped up in humor or acumen. It’s these words of wisdom that linger with us, that come out in colloquial moments among friends, that build our own character.

“After Ruth died and the railroad stopped runnin’, the café shut down and everybody just scattered to the winds. It was never more’n just a little knockabout place, but now that I look back on it, when that café closed, the heart of the town just stopped beatin’. It’s funny how a little place like this brought so many people together.”

* * *

Brenda Sawatzky is a relatively new, unpublished writer hailing from the wide-open prairie spaces of southeast Manitoba. She and her husband of thirty-one years are self-employed and parents to five kids (two ushered in by marriage). She is presently working toward fiction and non-fiction writing for magazines and manages a personal blog.

A guest post by Brenda Sawatzky.