Guest Post by Billie Millholland

When I told a friend I was doing a blog piece that championed steampunk stories, she sighed deeply. “Are you sure you aren’t a little late?” She thinks the steampunk genre reached its zenith in 2009/10 with a glut of excellent books like Cherie Priest’s Boneshaker and Dreadnought; Gail Carriger’s Souless, Changeless and Blameless, the first three books of the Parasol Protectorate; Jay Lake’s Pinion; and The Strange Affair of Spring Heeled Jack by Mark Hodder to name a few. She’s not the only one who feels that steampunk has become so mainstream it’s doomed to wither on a vine of mediocrity.

When I told a friend I was doing a blog piece that championed steampunk stories, she sighed deeply. “Are you sure you aren’t a little late?” She thinks the steampunk genre reached its zenith in 2009/10 with a glut of excellent books like Cherie Priest’s Boneshaker and Dreadnought; Gail Carriger’s Souless, Changeless and Blameless, the first three books of the Parasol Protectorate; Jay Lake’s Pinion; and The Strange Affair of Spring Heeled Jack by Mark Hodder to name a few. She’s not the only one who feels that steampunk has become so mainstream it’s doomed to wither on a vine of mediocrity.

I’m not blind to the tsunami of pathetically thin, steampunkish novels bursting bookstore shelves under nearly every category label from bodice-ripper romances to futuristic space adventures. Copycat themes that descend into cliché are inevitable following the advent of any literary innovation, but they are not always an indication of waning popularity. Steampunk stories are still alive and well in the literary world because they offer more than just an entertaining adventure.

What attracts good story tellers to the steampunk genre is not so much the clank and clatter of gears and springs, as intriguing as that is; the pull is bigger than that. I think it’s partly the recognition of a general global anxiety in the wake of decades of plastic, throw-away everything. An anxiety that’s soothed by metaphors of important inventions constructed out of noble, solid materials and forever repaired by a regular person in a shed behind the house. It’s the hope embodied in the notion of the revival of the backyard mechanic.

If anachronistic steampunk images, wrought of leather, glass and metal, were simply expressions of a nostalgia trend,  then steampunk fiction would have a dim future. It would fade into the shelves of historical fiction, still somewhat satisfying, but not really remarkable. Fortunately, the appeal of a good steampunk story goes deeper than the thrill of an airship piloted by a goggle-wearing aviatrix.

then steampunk fiction would have a dim future. It would fade into the shelves of historical fiction, still somewhat satisfying, but not really remarkable. Fortunately, the appeal of a good steampunk story goes deeper than the thrill of an airship piloted by a goggle-wearing aviatrix.

The appeal of a good steampunk story emerges in part from an empowering maker spirit; the clever ingenuity of DIY craftsmanship that flaunts the notion that anyone can build a flying machine and echoes the sentiment that gave birth to the open-source movement. It’s found in flipping the finger at the rigid conventions and stagnant protocols of a familiar puritanical past, the choke hold of which is still present today. It’s welcomed by those numbed by the tedium of relentless modern consumerism. A good steampunk story fuels a longing for an individualistic, break-away adventure. It encourages a smug satisfaction in heroic self-reliance. Steampunk is the cheeky tendon that connects a cynical present to an equally flawed, yet more colourful and idealistic past.

The industrial frenzy of the Victorian era is a natural mind worm that darts from neuron to neuron, bouncing off the hard curves of the skull like jolts from fresh morning coffee.

The emergence of wild and wonderful technology during the era of steam parallels the whirl of constantly changing technology today. Both are exciting, seductive and frightening. There is still room for good stories that rescue us from the latter by taking us to the former – a world we wish had been.

As recently as March 2013 “Cowboys and Engines“, a steampunk movie idea received crowd sourced funding through kickstarter. The maker spirit is at work here on all levels. Steampunk is about finding alternative ways of thriving in a world of megalithic institutions. Steampunk is for anyone with a maker spirit. It invites glorious literary experiments with giddy mash-ups. It encourages collaboration. Steampunk artists, writers, crafters, inventors, role players breathe life into an arts community forsaken by fiscally paranoid governments. Steampunk allows us to explore the past while contemplating the future. We are a tool-making species and steampunk reminds us how far we’ve strayed from our roots.

***

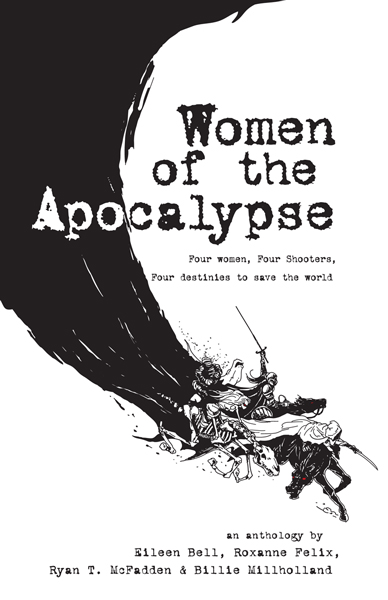

Billie Milholland was first published in non-fiction (Harrowsmith magazine, Western

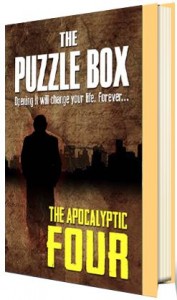

Billie Milholland was first published in non-fiction (Harrowsmith magazine, Western Producer People magazine and weekly newspapers in Alberta and British Columbia); then short fiction (in Canadian magazines & produced on CBC Radio Anthology); then novellas (a Time Travel Romance & one of four novellas in “Women of the Apocalypse“ (Aurora Award winner 2010). More recently she has had a Chinese steampunk story in Tyche Books anthology “Ride the Moon“ and is looking forward to seeing another short story in the “Urban Green Man“ anthology and another novella in “The Puzzle Box“, both coming in August 2013 (both from EDGE Science Fiction and Fantasy Publishing).

Producer People magazine and weekly newspapers in Alberta and British Columbia); then short fiction (in Canadian magazines & produced on CBC Radio Anthology); then novellas (a Time Travel Romance & one of four novellas in “Women of the Apocalypse“ (Aurora Award winner 2010). More recently she has had a Chinese steampunk story in Tyche Books anthology “Ride the Moon“ and is looking forward to seeing another short story in the “Urban Green Man“ anthology and another novella in “The Puzzle Box“, both coming in August 2013 (both from EDGE Science Fiction and Fantasy Publishing).