Does your story have the potential to be a big blockbuster? Will it ever be possible to get your story on the screen? What makes a story good for an adaptation?

Like the revolution which happened in the book industry, from book stores to ebooks, from big and medium press publishers to indie publishing, the film industry is undergoing a similar revolution. Why?

- Production costs have plummeted

- Post-production is cheap – there are many options for picture and sound editing software

- Distribution is available on several web sites or you can host your own

These changes have increased the opportunities for your story to be made into a movie.

Yes, your story, novel or short, can be scripted for the screen, whether it’s the big screen or a small one, or on the internet. It’s a big undertaking, but it can be done. Consider this though: not everyone is a writer and there are people who are looking for scripts for the small screen. For example, NetFlix has created a world of story production that wasn’t previously available. Production companies of all sizes, including independent producers, are looking for scripts so there are opportunities outside of Hollywood. Film festivals are resplendent with short films and they’re a good venue through which to get noticed – for you the writer and the producer.

When I write, I always see my stories as a movie. But does that mean my stories can be adapted into a movie? I needed to know so I took an online course with famed screen writer Bill Rabkin. Many of my points and examples are taken from that course. Thank you Bill! I knew that a good story is necessary, but what makes a story compelling enough to be made into a movie? Many of the things we know about good writing are also true in scripts, but here are a few things to be aware of when writing a script:

1) A great concept which makes the audience ask What happens next? is a must. An example: A nerdy teenager is bitten by a radioactive spider and gets superpowers.

2) Compelling characters embody what your story is about and are defined by his or her central conflict. All character details must relate to conflict because character is conflict and conflict is character. The only way we understand any character is by the choice he or she makes in pursuit of a goal.

3) Film is a visual medium much like a cartoon with a caption. This means that the internal monologue, the heavy thinking, all the pages of lovely prose, and all the long passages of dialogue are gone! Everything must be conveyed externally. In short – write what can be seen. Therefore, the conflict, the choices a character makes must be conveyed externally.

4) Most films follow the Three Act Structure: ACT 1 the set up with a disorganizing event (which can happen off screen and sometimes isn’t revealed until the end), the central problem, and inciting incident (which kicks the story into motion) which ends in a major turning point in the plot(25 pages); ACT 2 the complications with a major turning point in the middle with a big reversal. It doesn’t simply continue the ideas found in Act 1 – it explores and enriches them thus taking on depth and meaning/theme (50 pages); and ACT 3 the resolution (25 pages). And yes, movie scripts are approximately 100 pages long. The most important thing to know about structure is that following structure by itself doesn’t guarantee a good script – it is used to convey the meaning of your story.

4) Scripts have a format which must be followed exactly. There are lots of examples online but it’s easiest to use software. For free writing software check out programs like Celtx.

Now that we have some of the basics, let’s talk about adaptations. We’ve all seen some that work and others that don’t. Adaptations don’t work for me, not because of plot or setting changes, but when characters aren’t close to what I imagined when I read the book. For example, I was disappointed in a made for television movie of The Walkers of Dembly, an Agatha Raisin novel by MC Beaton. The protagonist was very different from the one I had imagined (in looks and character) in the series and another favorite character was missing. The convention of the cozy mystery weighs heavily on character and if those personalities are too different from the book, knowledgeable viewers won’t be happy. If plot or setting changes occur, viewers tend to be more forgiving if the characters’ actions have a ring of truth about them. That is why some stories adapt well to television series and can go for seasons ‘based on’ the original on with plots which were never written in the books. Other series that have adapted successfully due to acting, script writing and direction are Murdoch Mysteries, Rizzoli and Isles and the British drama series, Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot.

Character and dialogue (along with setting) create the tone of the movie and getting that tone right is what makes for a good adaptation. Screenwriter Erin Cressida Wilson’s expressed it best when she said “…it’s really all about figuring out what I can add to create a tone that‘s filmically the same as the literary tone, because tone is the most important thing, and I almost think you could do anything you want, after that.” Wilson wrote the script for The Girl on the Train and the reviews have been great. You can find Andrew Bloomenthal’s interview at SCRIPT (Division of The Writers Store) by clicking here: INTERVIEW: Screenwriter Erin Cressida Wilson Brings ‘The Girl on the Train’ to Life.

We’re familiar with novels and trilogies and series making it to television or to the big screen. Take heart short story writers – if you have a compelling concept, memorable characters mired in conflict, and great plot, your concept can make it to the screen too. Check out Ted Chiang’s sci fi story “Story of Your Life” then see the movie Arrival. After you’ve compared the similarities and the differences, and see how the story was adapted, perhaps you’ll be inspired to adapt your creations for the screen.

It’s not the big jackpot or nothing! There are as many opportunities in books and film as we have imagination. We’ve been practicing the art of storytelling and now all we need to do is to learn the conventions of script writing and the film industry and a whole new world of possibilities will unfold.

Leveraging your IP into a film or miniseries adaptation is one of the best ways to make money as a writer. Not only can you get the income from licensing your rights, but having a major motion picture or miniseries made will give your works access to a much larger audience. The phrase “based on a bestselling series” is good for both sides of the business. It attracts attention to the movie, but it will also give a healthy boost to your book sales leading up to the release.

Leveraging your IP into a film or miniseries adaptation is one of the best ways to make money as a writer. Not only can you get the income from licensing your rights, but having a major motion picture or miniseries made will give your works access to a much larger audience. The phrase “based on a bestselling series” is good for both sides of the business. It attracts attention to the movie, but it will also give a healthy boost to your book sales leading up to the release. However, film has significant advantages in its ability to employ complex visual elements. As authors, we rely on the power of our language to inspire our audience’s imaginations. Film, on the other hand, relies on the skill of the special effects, costuming, and set design teams as well as the training of the actors. When you write a book, be sure to feed those teams with strong, iconic visuals. Furthermore, a five second panning shot can show the thousands of tiny details that would take an author five pages to describe. You get the same effect without having to worry about slowing down pacing.

However, film has significant advantages in its ability to employ complex visual elements. As authors, we rely on the power of our language to inspire our audience’s imaginations. Film, on the other hand, relies on the skill of the special effects, costuming, and set design teams as well as the training of the actors. When you write a book, be sure to feed those teams with strong, iconic visuals. Furthermore, a five second panning shot can show the thousands of tiny details that would take an author five pages to describe. You get the same effect without having to worry about slowing down pacing. Though many of Dresden’s spells were fantastic, they were also remarkably low budget. Making the pentacle necklace glow? Not hard. Blasts of fire would take more skill, but can be done in a number of film editing softwares. As can Bob’s glowing campfire sparks.

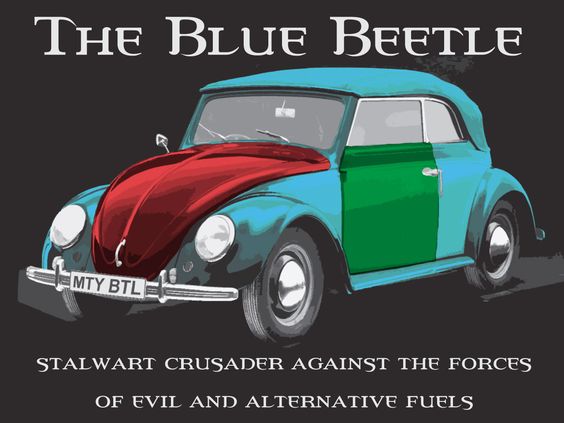

Though many of Dresden’s spells were fantastic, they were also remarkably low budget. Making the pentacle necklace glow? Not hard. Blasts of fire would take more skill, but can be done in a number of film editing softwares. As can Bob’s glowing campfire sparks. For example, the directors of the Dresden Files TV series chose to eliminate the beloved Blue Beetle in favor of a Vietnam era jeep. While the Blue Beetle provided good comic relief in the books, it would have been an extremely difficult set piece to shoot. The director’s camera angles would have been severely limited by how small and enclosed the vehicle was. The only way to get around this problem would be to have multiple Beetles – the first for exterior shots, and a second that was partially disassembled accommodate to the cameras for the interior shots.

For example, the directors of the Dresden Files TV series chose to eliminate the beloved Blue Beetle in favor of a Vietnam era jeep. While the Blue Beetle provided good comic relief in the books, it would have been an extremely difficult set piece to shoot. The director’s camera angles would have been severely limited by how small and enclosed the vehicle was. The only way to get around this problem would be to have multiple Beetles – the first for exterior shots, and a second that was partially disassembled accommodate to the cameras for the interior shots.