Interview with author Jayne Barnard and editor Adria Laycraft.

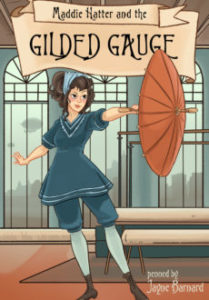

An author’s worst fear can be about getting their work edited or critiqued by an editor, an agent, or even a critique group. Yet, whether indie publishing or working with a large or small press, the process of getting edited is critical to make the story the best it can be. I had the fortune to meet over dinner with award winning author Jayne Barnard and her editor Adria Laycraft to chat about what makes their relationship work. Adria edited Jayne’s latest novel Maddie Hatter and the Gilded Gauge.

Ace: Jayne, what is your worst fear when working with a new editor?

Jayne: You really have to take a leap of faith that the person is coming into it has the right spirit, that they’re not looking to score off you or browbeat you into doing what they want with your story.

Jayne: You really have to take a leap of faith that the person is coming into it has the right spirit, that they’re not looking to score off you or browbeat you into doing what they want with your story.

Ace: It’s not about ego, it’s about making the story as good as it can be.

Jayne: Yes, and it can come apart very quickly if either the editor or the writer is acting superior. You see that in so many series. The example of Harry Potter comes to mind. The first three books when J.K. Rowling was a new author were clean, tight, and tidy, and they’ve got cool structure. The fourth book could have been cut by 10% off the top and the fine details polished. Did that not happen because of Rowling or because the publisher felt that they didn’t need to make the investment? We’ll never know.

Ace: Adria, what is your fear when taking on a new client?

Adria: That’s a loaded question. In this case, it’s about not only doing the best for Jayne, but for the publisher who hired me, Tyche Books. The big thing for me in a new relationship is being understood.

Ace: Understood?

Adria: You know how easy it is to misunderstand the tone and the body language in a text? Are they saying: I’ll be right there, or I’ll be right there? But when we speak, we use different intonations to convey specific meanings. As an editor, I have to figure out the author’s intention and if that intention is being conveyed. So, when I make changes and suggestions, my fear is about being misunderstood and upsetting the author. If that happens, it’s difficult to achieve our common goal to make the story its best.

Adria: You know how easy it is to misunderstand the tone and the body language in a text? Are they saying: I’ll be right there, or I’ll be right there? But when we speak, we use different intonations to convey specific meanings. As an editor, I have to figure out the author’s intention and if that intention is being conveyed. So, when I make changes and suggestions, my fear is about being misunderstood and upsetting the author. If that happens, it’s difficult to achieve our common goal to make the story its best.

Ace: How do you make it the decision whether it’s grammar or the author’s voice?

Adria: I don’t make the decision. I point it out to the author and they make the decision. It’s their book and their choice. For example, I pointed out some things to Jayne which weren’t technically correct and let her decide.

Jayne: Like capitalizing the seasons. Adria noted that technically this wasn’t correct and asked if I wanted to do this. That’s a very Victorian style that I deliberately used.

Adria: Whereas an editor with a nice big ego <<grins>> charges in and fixes things so that it’s technically accurate but ends up ruining the story.

Jayne: But a good editor can also help make the story richer. For example, Adria and I are working on foreshadowing and subtext. Foreshadowing and subtext build things up from the very beginning. One word here or three words there, and then the choice of colour for a hair bow – all the things which build up a character or subplot subconsciously. Individually, they don’t mean much but all together they make the story amazing. What happens when you over-edit, and you can over-edit yourself <<laughter – we’ve all done that!>> you edit out the things that make your work colourful and strong. In effect, you’ve flattened your work. It becomes more of the same, less whimsical. When you have an editor really into your work and I’ve only discovered this because Adria is the best editor I’ve ever had…

Adria: Now I’ll have a swollen head. <<peals of laughter!>>

Jayne: …she points out the things that I can exploit to make the story richer. Sometimes, though, I think, “Hey, I could do this with it!” and then Adria asks if it’s relevant and if it serves the story.

Ace: You’re talking about danglers which should be either eliminated or exploited?

Adria: They’re the elements that never get properly tied up in the end. Some are so cool that you have to find a way to use them. But always you have to ask if you need them and if so, how you’re going to use them.

Ace: The question is: Is it a gem you need to polish or is it a stone you need to throw away?

Jayne: It’s more like throwing a ruby into the gravel. To me it’s just coloured glass, a whimsy, until Adria she points out that it’s really a ruby, dusty and uncut, but a gem. The question then becomes, does it need it be faceted and polished to its full potential, or does it need to be removed because it’s a distraction from the greater story?

I also think it helps to be edited by someone who’s writing a speculative fiction because I know her ego isn’t invested in my work, but her own.

Adria <<grinning>>: My ego is also invested in how well your book does, Jayne.

Jayne <<laughing>>: Because your name is on it too!

Adria: And I want other people to hire me to edit too. I love editing. I love helping other people realize the dream of what they want their book to be! I’d like to read something that Jayne texted to me recently: the crux of a good editing relationship is the free flow of information and ideas like a conversation between professionals. It isn’t hard to keep it professional, is it?

Jayne: No, it isn’t.

Adria: Then I said, the key for the editor is to help an author create the best version of the story they want to tell and to remember not to start rewriting their words.

Jayne: Agreed.

Adria: I’ve personally had that experience with other editors and in critique groups and all the years of critiquing others and being critiqued. The key thing that helps me be a good editor now is knowing not to over critique or to over edit, and especially to not try to rewrite the person’s story for them.

Jayne <<laughing>>: No matter how tempting it is!

Adria: And sometimes it’s really tempting! But, it’s their story and all I can do is make suggestions. It’s not my story to write. That was the big learning curve for me to become a good editor.

Ace: Advice to new writers would be that to learn how to work with an editor go to critique groups get critiques done, and give critiques. That teaches us how to be respectful of an editor and which fights are the important fights to pick.

Jayne: That’s a good point: which fights to pick. Now, I’ve been fairly lucky with Adria because she reads and writes in my genre. She thinks it’s all fine fun <<more laughter>> so in that sense we have some fundamental compatibilities in looking at the project. Adria challenges me to make it better, deeper, richer – I’ve never had an editor do that before. They focused on making it technically correct or easier for the reader to understand, but not creatively greater than before.

Ace: The special sauce of this relationship is mutual respect with a common goal which is to make the book the best that it can be.

Adria: Yes, but to really make the relationship work, my advice for new authors is to be professional, and don’t get defensive. Take the comment and go sit with it for a while. When you kick into defensive mode, I can’t help you. You won’t see what I’m trying to point out if all you’re going to do is to defend why there has to be a ruby in the gravel.

Ace: Perhaps if you have to defend something, then maybe you haven’t expressed it clearly as a writer. If your editor isn’t getting it, then no one else is going to get it.

Adria: If you have to explain it and defend it, then that’s why I’m pointing it out – because there’s an issue.

Jayne: And from the author’s side, I would say that if the editor says something you really disagree with, don’t answer right away. Go for a walk, go whack down some weeds in the back yard, or sound off to your best friend. Then, as a professional, set aside your feelings and think about what those comments mean for the story.

Ace: Some reader will always tell you that you’ve got it all wrong and they may not be so nice about it. But with an editor, you have the opportunity to consider the comments and make changes. Once published, you don’t have an opportunity to change the manuscript.

Jayne: Readers paid for your book in money and time so they have the right to their opinion even if they totally missed what you were trying to say.

Adria: If you’re a new writer, even an established writer, and you’re getting the same comment from 5 out of 8 people in a critique group, then there is a problem. If it’s just one, and you disagree with it, you have a right to disagree. If you’re getting the same thing again and again, then you must look at it. For instance, early on in my writing, I was told that my characters were passive. It took me a long time to hear that, to stop being defensive about it. I was trying to tell the story of characters who were passive and it didn’t work. When I stopped being defensive, I realized they were right.

Jayne: It’s all about the outcome – the best words in the best order. Unlike the football player or the stage actor who have to make it perfect in the moment, with no do-overs, writers have the leisure to consider what words we’re putting in what order. There’s no excuse for a writer to publish a shabby story.

Ace: Thank you both for your candor and your time. Now, when I’ve transcribed this interview, I’ll send it to you both for your editing.

Adria: But you’re the interviewer, you’re supposed to edit it.

Ace: As a good editor, I know that these words are yours and not mine and only you can have the last say!

Jayne: Touche!

<<peals of laughter>>

Adria is a grateful member of IFWA (The Imaginative Fiction Writers Association) and a proud survivor of the Odyssey Writers Workshop. She is also a member of the Calgary Association of Freelance Editors (CAFÉ). Her biggest claim to fame as an editor is Urban Green Man, which launched in August of 2013 and was nominated for an Aurora Award. Look for her stories in Orson Scott Card’s IGMS, the Third Flatiron Anthology Abbreviated Epics, the FAE Anthology, Tesseracts 16, Neo-opsis, On-Spec, James Gunn’s Ad Astra, and Hypersonic Tales, among others. To learn more about her work and editing services, contact Adria at adrialaycraft.com.

Adria is a grateful member of IFWA (The Imaginative Fiction Writers Association) and a proud survivor of the Odyssey Writers Workshop. She is also a member of the Calgary Association of Freelance Editors (CAFÉ). Her biggest claim to fame as an editor is Urban Green Man, which launched in August of 2013 and was nominated for an Aurora Award. Look for her stories in Orson Scott Card’s IGMS, the Third Flatiron Anthology Abbreviated Epics, the FAE Anthology, Tesseracts 16, Neo-opsis, On-Spec, James Gunn’s Ad Astra, and Hypersonic Tales, among others. To learn more about her work and editing services, contact Adria at adrialaycraft.com.

After 25 years writing short mystery fiction, Jayne shifted to long-form crime with the YA Steampunk romp, MADDIE HATTER AND THE DEADLY DIAMOND (2015), a finalist for the BPAA and the Prix Aurora. The second Maddie Hatter Adventure, MADDIE HATTER AND THE GILDED GAUGE, (Tyche Books, May 2017) is on shelves now and the third is due out this fall Her contemporary suspense novel, WHEN THE FLOOD FALLS, won the Dundurn Unhanged Arthur in 2016 and is being published by Dundurn along with two sequels. Jayne divides her year between the Alberta Rockies and the Vancouver Island shores.

After 25 years writing short mystery fiction, Jayne shifted to long-form crime with the YA Steampunk romp, MADDIE HATTER AND THE DEADLY DIAMOND (2015), a finalist for the BPAA and the Prix Aurora. The second Maddie Hatter Adventure, MADDIE HATTER AND THE GILDED GAUGE, (Tyche Books, May 2017) is on shelves now and the third is due out this fall Her contemporary suspense novel, WHEN THE FLOOD FALLS, won the Dundurn Unhanged Arthur in 2016 and is being published by Dundurn along with two sequels. Jayne divides her year between the Alberta Rockies and the Vancouver Island shores.

Website: jaynebarnard.ca; Facebook: @MaddieHatterAdventures;

Twitter: @JayneBarnard1