One aspect of character that can be hard to pin down is: How funny should they be?

One aspect of character that can be hard to pin down is: How funny should they be?

Most of us aren’t comedy writers. We write fantasy or science fiction or horror or (input genre), but that doesn’t mean humor doesn’t have a place in our stories.

People draw upon their sense of humor in real life, even in dire circumstances. It helps relieve tension and to cope. We don’t need to become the next Terry Pratchett, but sometimes a little humor is the best way to deal with the difficult situations we’re bound to drop our characters into.

Everyone loves a sense of humor. Does our character have one?

Humor has a scale, just like all the other attributes we’re defining for our characters, just as important as their fighting skills, how much they love their mother, and whether they respond to small animals by wanting to pet them or to eat them. We just don’t think about it that way as often.

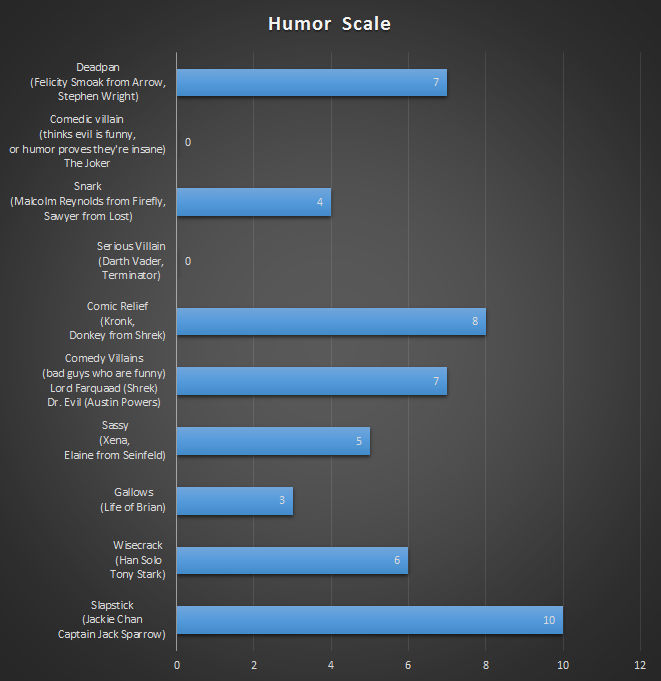

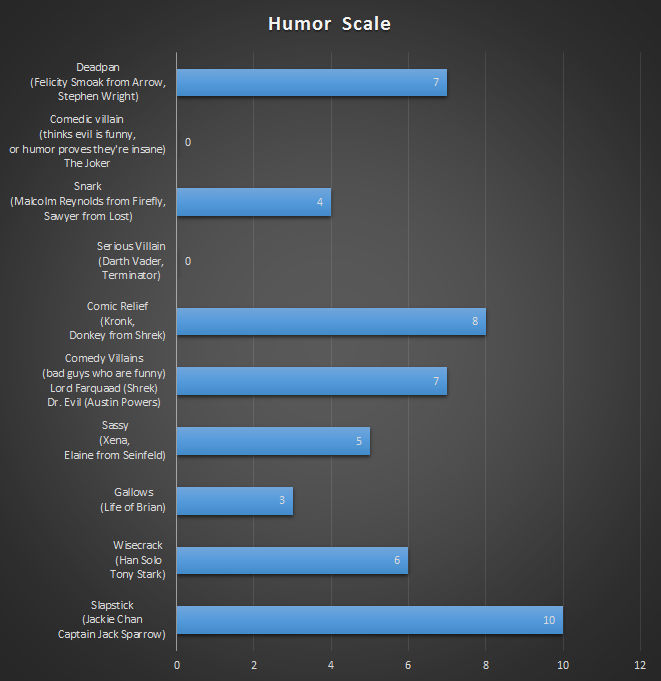

So I’ve designed a Humor Scale to demonstrate the types of humor we can assign to our characters.

- Slapstick (10) – Pure comedy. Take some ibuprofen because your stomach’s going to hurt from laughing so hard.

- Comic Relief (8) – Usually not your main protagonist. These are the side-kicks that we love to laugh at.

- Deadpan/dry (7) – They say funny things, but in a serious way.

- Comedy Villains (7) – They’re bad guys, but they make us laugh instead of scaring us.

- Wisecrack (6) – Always have a comeback, a great one-liner, no matter how dire the situation.

- Sassy (5) – Cheeky, and full of spirit. Often get into trouble as a result.

- Snark (4) – Sarcastic, snide.

- Gallows humor (3) – The more dangerous one’s job, the more refined their gallows humor. Think of the group of crucified criminals in Monty Python’s The Life of Brian singing, “Always look on the bright side of life.”

- No humor (0) – These are often your serious villains who burned all humor out of their system.

- Comedic villain (0) – They’re the bad guy, but they think evil is funny. Their sick humor either demonstrates a lack of understanding of the gravity of what they’re doing, or proves they’re insane.

Here’s the Humor Scale in graph form, with examples to illustrate each category.

We can apply the various categories in all kinds of situations. Some examples include:

- Jokes. These can be woven in just about anywhere.

- Situational humor. The entire scene is inherently funny (your super-buff warrior hero is stuck in a cupcake bake-off against the evil overlord)

- Dialogue. Great place for wisecracks, snark, sass, and gallows humor.

- A funny outlook on life. Either irreverent, bizarre, or just a little bit off. Any of these can produce humorous situations and dialogue. Something funny, and yet totally in character.

- And of course, slapstick lies in a realm all its own. This is pure comedy. Some characters just have to fall down and break things wherever they go.

In all of these instances, there are commonalities. Surprise is the secret to humor, and usually there’s some kind of set-up, then the punch-line that adds the surprise, the twist, generating the laugh.

Humor often pushes things to the extreme. Think the intro to Captain Jack Sparrow. Standing atop the mast of his ship is a great epic image. Then comes the comedic twist when we learn it’s really a small boat and he’s standing atop the mast because the ship is sinking out from under him.

So let’s talk specific application.

When I first started writing, I included only a little humor in my stories. Even the first drafts of my YA fantasy story, Set in Stone, remained too serious. With some self reflection and encouragement from family, I decided the story needed humor to work. So I rewrote 80% of the novel, making dramatic changes to the plot structure and how I approached it. I ratcheted up the humor while still maintaining an epic feel to the story. It was my first foray into humor-laden fantasy, and response from beta readers is overwhelmingly positive. The novel will be released this spring.

With my urban fantasy novels, I toned down the humor, but I’ve been experimenting with sliding characters along the humor scale, depending on which effect I’m looking for.

It’s not as hard as I first feared. Humor isn’t the story. It’s just another layer, and you can shift characters along the humor scale pretty easily once you determine what effect you’re looking for.

In a recent editing pass over an epic fantasy novel, I decided to shift the protagonist a couple of notches up the scale. So I mixed in a little snark and dry humor, which helped him come across as more experienced, more resilient, and less emotional. The story as a whole is unchanged, but his outlook on life, and his responses to some of the crazy events he’s experiencing works so much better.

In essence, I shifted him away from the Luke Skywalker end of the scale and more toward Han Solo. Luke is young, idealistic, and inexperienced while Han is tough, world-wise, and irreverent. They’re both heroes, but they approach life and trials differently. I applied a little of Han’s unflappable attitude and great one-liners.

In essence, I shifted him away from the Luke Skywalker end of the scale and more toward Han Solo. Luke is young, idealistic, and inexperienced while Han is tough, world-wise, and irreverent. They’re both heroes, but they approach life and trials differently. I applied a little of Han’s unflappable attitude and great one-liners.

In The Empire Strikes Back, after losing his hand and learning the evil overlord of the universe was his father, Luke’s response always seemed more whiny than heroic:

“Nooooooo! I’ll never rule the universe with you.”

My character had reacted more like that. Now he could now respond more like Han Solo who, after being tortured, just said, “I feel terrible.”

Or who snapped, “Never tell me the odds,” when flying into an asteroid belt.

Or, when Leia confessed she loved him just prior to his getting frozen in carbonite, he glibly replied, “I know.”

Another example of the effect of the Humor Scale decision is comparing Battlestar Galactica to Firefly. Both have spaceships, fighting, life-and-death situations but, where Firefly is enhanced by the humor woven into it – making it a cowboys in space adventure – Battlestar Galactica was left very straight-laced – a little too much so in my opinion.

So play with this layer. After writing your story and making sure all the other elements are in place, check where each character falls on the Humor Scale, and where that takes your story as a whole. Then decide if that’s where you want it. Perhaps poll some early readers and discuss if the story would benefit from either more or less humor.

Tweak accordingly, and have fun with it.

* * * *

Here are a few humor-related links you might be interested in:

Scott Adam’s Dilbert blog, where he talks about writing humor.

The Writer’s Dig by Brian Klems – Another good blog post, with links to other articles.

Tabloid Reporter to the Stars – This is a short story recommended to me as an example of one that successfully added humor. I haven’t read it yet, but plan to.