TV storytelling has changed with the advent of VCRs, DVDs and streaming services. In the golden age of TV, it was much more common for each episode of a TV show to be a self-contained story.

TV storytelling has changed with the advent of VCRs, DVDs and streaming services. In the golden age of TV, it was much more common for each episode of a TV show to be a self-contained story.

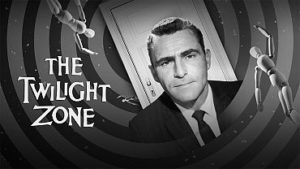

The reason is simple: showrunners couldn’t presume that viewers had been able to watch the previous episodes. If you were busy during the show’s airing time, then you missed the show. So, it made sense for each episode to stand alone. Title sequences introduced new viewers to the show’s characters, theme and mood. Even if you’d never seen a show before, you could get a pretty good idea what it was about before the day’s episode started. (And title sequences are getting shorter these days, or being left out entirely, now that most viewers no longer need them to learn about the show they’re about to see.)

The problem with episodic storytelling is that it’s more difficult to show long-term character development, or to give events permanent consequences. In its purest form, the end of the episode presses the reset button, returning the characters to the status quo at the beginning of the next episode. Still, some shows developed a certain sense of continuity: origin episodes, introduction of new characters or departure of old ones, key events in season finales.

With the advent of the VCR, people could record shows and watch them later at their convenience. And now, with streaming services, it’s become common for viewers to “binge” on a show and watch the entire season over the course of a few days.

(This is not to say that the golden age of TV didn’t have serials–soap operas, anyone?–or that there isn’t great episodic TV being made right now. )

But general trends changed when it became easier for people to keep up with their favourite shows. When data suggested that people enjoyed viewing shows in a single sitting (or two or three), showrunners naturally made shows catering to those kind of viewing habits. There’s now a strong trend towards “bingeable” shows – long running serials that tell a multi-thread story over the course of a season, and an even bigger story over the course of a series. Actions have consequences, and characters grow and change – but it’s rare for a viewer to pick a random episode in the middle of a series just to “check it out,” now that it’s easier to start at the beginning.

When you’re writing a novel series, which model do you want to follow?

In part, it depends on genre. For example, if you’re writing a category romance novel series, it’s often expected that a new reader should be able to pick up a book at any point in the series and enjoy the story. Additionally, romance stories derive their tension from showing how the hero and heroine get together–tension that’s hard to show once they’re an established couple. As a result, category romance series have developed a certain pattern. Each book in the series takes place in the same world, but each book (usually) focuses on a new hero and heroine. The supporting characters are often either the heroes/heroines of previous books, or future hero/heroines of upcoming stories. As a result, fans are able to return to a world they love, while new readers won’t be lost if they aren’t familiar with the supporting characters from previous books, and the primary tension is still focused on watching a couple overcome their obstacles to be together. However, this formula makes it difficult to show character relationships growing and changing beyond the book that the characters “star” in.

On the other hand, some series all but require you read them in order, or you’ll be lost continuity-wise. For myself, I love a big, ongoing, developing story where characters’ actions have consequences, and the plot unfolds based on the choices the characters made previously. But this technique makes it harder for new readers to “jump in” in the middle.

And some series walk a middle line. Each book is a self-contained arc, but if you put them together, you’ll also see a series-long story arc developing. For example, in some mystery series, a new mystery gets solved in each book, but as the series progresses, the main characters change, develop, and grow, giving the series a sense of continuity and ongoing development.

In large part, it depends on what you as a writer want to do. Do you want to write a series where each book focuses on a different character in the same universe? Do you want the flexibility to add “new adventures” if the series takes off?

Or do you have a long-term vision for a story that’s too long for just one (or three, or more) books to hold? Do you want to show a character growing and changing over the long term, and do you believe that you can convince audiences to care about this character, to choose to spend time in their company over and over again?

If the first book in a series hooks a reader, they’re likely to come back for more—particularly when they feel that the story is “going somewhere” and that each book “matters” because events have consequences. But there’s also something to be said for a format that’s welcoming to new readers, and doesn’t require them to put Book 4 back on the shelf and go looking for Book 1 in order to understand what’s going on. There’s audiences for both types of series (as well as the middle gorund) so choose what method best suits your genre and the story you want to tell.

About Mary: