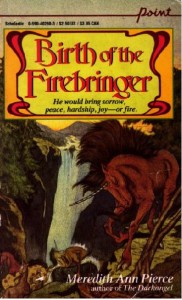

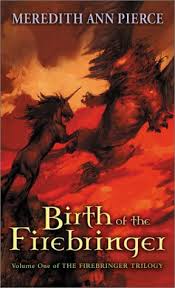

Unicorn stories. The topic seems geared towards wish-fulfillment for little girls, a more fantastical rendition of the “horsey” books so popular in the 1980s. As a child I consumed mountains of these books, about both horses and unicorns, until I stumbled across a completely different animal: Birth of the Firebringer by Meredith Ann Pierce.

Unicorn stories. The topic seems geared towards wish-fulfillment for little girls, a more fantastical rendition of the “horsey” books so popular in the 1980s. As a child I consumed mountains of these books, about both horses and unicorns, until I stumbled across a completely different animal: Birth of the Firebringer by Meredith Ann Pierce.

This is not a story about what it’s like to ride a unicorn. This is a story about what it’s like to be one.

From the first page I was catapulted into a world unlike any I’d ever imagined. There are no human characters in this book. The unicorns of the Vale are a people, a culture unto themselves (though notably not the only unicorn culture), and the narration is sprinkled with examples of their religion, their storytelling, their singing. The main character, Jan, is torn between a desperate desire to win the good regard of his father the prince, and to follow his own heart, even when it conflicted with his people’s traditions and teachings. This conflict leads him to question everything he was raised to believe: about his faith, his people’s history, and his destiny.

These unicorns don’t lounge about in meadows waiting for beautiful maidens to happen by. Their story is one of struggle: driven from their homeland by the wyverns, they settled in a Vale across the Great Grass Plain. As Birth of the Firebringer opens, their numbers have grown and they await the coming of the prophesized Firebringer, who will lead an army back to their ancestral lands to reclaim what is theirs.

Pierce layers the narrative with hints that the unicorns’ version of history might not be as true as Jan has been taught to believe. The legends, for example, always describe the Vale as “empty” when the unicorns arrived. Later, Jan will realize that the Vale was a hunting ground for the gryphon clans, and when the unicorns invaded and drove out the native game, the gryphons, as a people, suffered. I still remember the shock of realizing, along with Jan, that the antagonistic gryphons might actually have a legitimate reason for the attacks they launched against the Vale–something beyond a thirst for cruelty.

I was thunderstruck. And I wanted to tell stories like that. My play with My Little Ponies changed from saddles and bridles and combing hair into epic quests and wars against dragons, incorporating world-building, history and mythology, involving prophecy and politics and revelations. Unicorns were serious business. I no longer wanted to be a princess mounted on a unicorn. I wanted to see a world through a unicorn’s eyes.

I was thunderstruck. And I wanted to tell stories like that. My play with My Little Ponies changed from saddles and bridles and combing hair into epic quests and wars against dragons, incorporating world-building, history and mythology, involving prophecy and politics and revelations. Unicorns were serious business. I no longer wanted to be a princess mounted on a unicorn. I wanted to see a world through a unicorn’s eyes.

I was an adult before I realized that Birth of the Firebringer was in fact the first in a trilogy. Dark Moon addresses the question of humanity, previously only hinted at in Firebringer — an alien and powerful species that sees the unicorns as fabulous beasts. The Son of Summer Stars brings prophecies to fulfillment in a way no one imagined, and takes Jan from youth into adulthood.

The Firebringer Trilogy is classed as young adult fantasy, but reading the last two books as an adult, I have no reservations about recommending them to other adults. The story remains powerful, and the language beautiful. Pierce chooses words to enhance the conceit that the reader, along with Jan, is listening to a unicorn storyteller’s tale; and yet the tale remains easy-to-follow rather than getting bogged down by its own description.

If you’re ready to leave your humanity behind and take a look at the world from the point of view of a creature who is utterly unlike you – if you are ready to question your leaders, your faith, and your role in the world – if you are prepared to set aside the preconception that unicorns are fluff for little girls – then enter the world of Meredith Ann Pierce’s Firebringer Trilogy.