Honestly? I’ve never thought about tension while writing. I’ve thought about conflict a whole lot: overarching conflict, conflict between characters, conflict with the environment, etc. But I’ve never framed it in my mind as “tension.” After some thinking, I decided it wouldn’t be quite right to offer advice about something that I don’t tend to think about while writing. However, I have noticed it while reading. So in lieu of offering advice, I’ve put together a list of memorable stories that created tension in a very unique way that may help you in your own writing. The fun of creating tension doesn’t have to be all your characters’ doing. By honing in on your narrative voice, you can create tension between you and your reader using a variety of techniques.

Honestly? I’ve never thought about tension while writing. I’ve thought about conflict a whole lot: overarching conflict, conflict between characters, conflict with the environment, etc. But I’ve never framed it in my mind as “tension.” After some thinking, I decided it wouldn’t be quite right to offer advice about something that I don’t tend to think about while writing. However, I have noticed it while reading. So in lieu of offering advice, I’ve put together a list of memorable stories that created tension in a very unique way that may help you in your own writing. The fun of creating tension doesn’t have to be all your characters’ doing. By honing in on your narrative voice, you can create tension between you and your reader using a variety of techniques.

Tension Through Foreshadowing

In the classic book One Hundred Years of Solitude, Gabriel García Márquez sets up tension in the first half of his book by dropping the same line over and over: “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía remembered…” Instantly, the reader questions this. Aureliano before a firing squad? How did he get there? Also… Colonel? When does he become a Colonel? With this line, the author continues to keep these questions fresh in the reader’s mind, and the reader continues on with the book in order to get the answers to those questions.

In the classic book One Hundred Years of Solitude, Gabriel García Márquez sets up tension in the first half of his book by dropping the same line over and over: “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía remembered…” Instantly, the reader questions this. Aureliano before a firing squad? How did he get there? Also… Colonel? When does he become a Colonel? With this line, the author continues to keep these questions fresh in the reader’s mind, and the reader continues on with the book in order to get the answers to those questions.

Tension Through Speaking Directly to the Reader

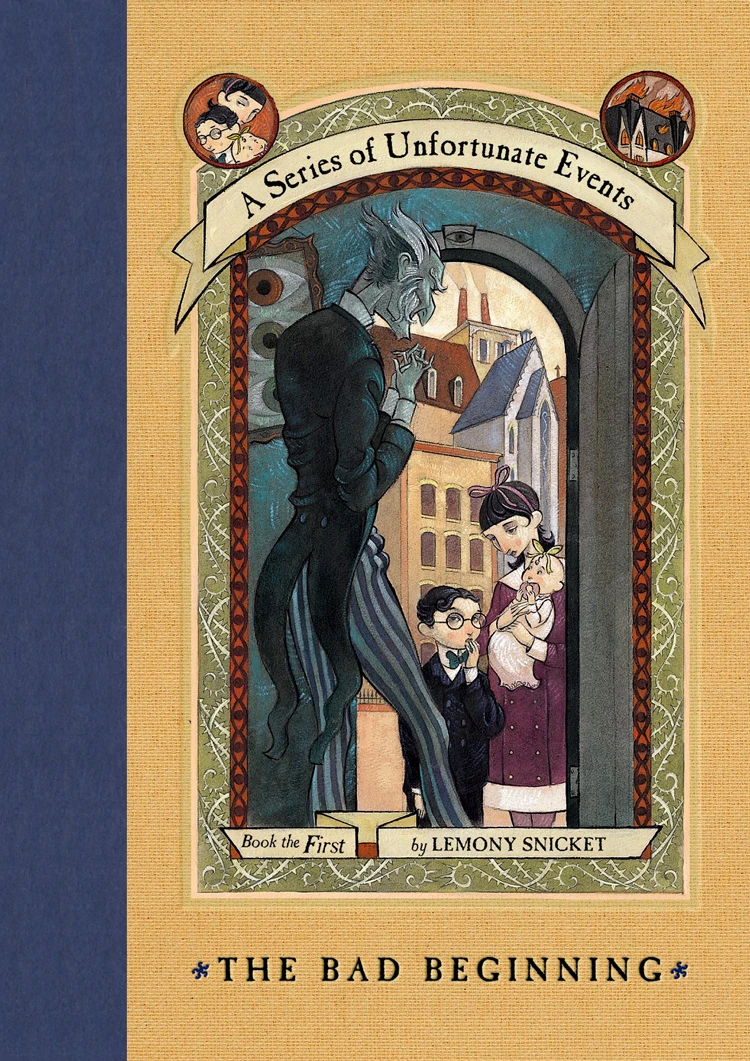

In one of the darkest children’s series out there, Lemony Snicket (Daniel Handler) adds a warning to the reader at the beginning of every book. In the very first book, he lays the land:

In one of the darkest children’s series out there, Lemony Snicket (Daniel Handler) adds a warning to the reader at the beginning of every book. In the very first book, he lays the land:

“If you are interested in stories with happy endings, you would be better off reading some other book. In this book, not only is there no happy ending, there is no happy beginning and very few happy things happen in the middle. This is because not very many happy things happened in the lives of the three Baudelaire youngsters.”

By doing this, Snicket sets expectations and creates tension between himself and the reader. The reader fights the warning, thinking this, a children’s book, couldn’t end so badly. And yet, Snicket promises a unhappy ending. But what could that ending be? How could something so terrible happen to these wonderful children?

Tension Through Story Structure/Switching Timelines

This technique is a favorite among Literary Fiction authors and moviemakers. The author has one character telling the story as they remember it, allowing them to be the narrator. However, the switches from past to present is up to the author. That means right when something happens, the author has the power to pull back to present time, have the narrator reflect for a time, and then go back into the action. This undoubtedly drives some readers nuts, but can we deny it causes tension? Nope! An example of this would be Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides, where our narrator, Cal, starts most chapters in the present, and then switches back to telling his grandparents’ and parents’ stories. The reader becomes anxious to see what’s going on in the present, and yet is forcibly taken to the past instead. This, in the best cases, builds tension by way of anticipation.

This technique is a favorite among Literary Fiction authors and moviemakers. The author has one character telling the story as they remember it, allowing them to be the narrator. However, the switches from past to present is up to the author. That means right when something happens, the author has the power to pull back to present time, have the narrator reflect for a time, and then go back into the action. This undoubtedly drives some readers nuts, but can we deny it causes tension? Nope! An example of this would be Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides, where our narrator, Cal, starts most chapters in the present, and then switches back to telling his grandparents’ and parents’ stories. The reader becomes anxious to see what’s going on in the present, and yet is forcibly taken to the past instead. This, in the best cases, builds tension by way of anticipation.

Tension, R.L. Stine Style

The master of ending a chapter on a cliffhanger is the incomparable R.L. Stine.

When I was growing up, I was afraid to read out loud in class. I’d stutter, and as anyone who has tripped in front of their crush knows, once you start falling, nothing can save you from making a fool of yourself. In order to combat this, my dad suggested we read aloud to one another each night. We chose Goosebumps, naturally, because who wouldn’t. We found we’d read for longer than either of us anticipated because we just HAD TO KNOW what happened in the next chapter. If that’s not tension, keeping your readers up way past their bedtimes, then I don’t know what is.

Remember that tension doesn’t have to lay on the shoulders of your characters every time. Consider taking some of the burden from them and messing with your readers’ minds yourself!