An interview with Jayne Barnard.

Jayne Barnard, a successful and award-winning author, says that participating in NaNoWriMo has been critical to her career. Not only was NaNo’s self imposed discipline important to learn, but it was also instrumental in launching her career. I interviewed Jayne to find out how NaNoWriMo influenced her.

#1 What did you learn by participating in NaNoWriMo?

I learned:

a) to outline (more on this later);

b) to clear my schedule of distractions. Otherwise I’ll quite happily spend all week visiting with people in person or online, reading library books because they have to go back soon, shot-gunning series on Netflix, cleaning closets.

b) to clear my schedule of distractions. Otherwise I’ll quite happily spend all week visiting with people in person or online, reading library books because they have to go back soon, shot-gunning series on Netflix, cleaning closets.

c) that I need to reward myself for meeting my goals. The first time I did NaNo, I didn’t know to set up a personal reward structure. As the story got complicated, it got progressively harder to force myself back to the keyboard. I think I gave up around November 13th that first time.

I’ve learned since that I can lure myself through a lot of work by setting a daily word count and promising myself a couple of episodes of my current favourite show once that word count is saved on the page/screen. At 5,000 and 10,000 and 25,000 words I lined up progressively larger rewards, including going out to a movie and going out for supper (see ‘distractions’). Otherwise, I had to be at home working until I’d met the goal.

#2 NaNo requires working under pressure. Is there a lot of pressure in working with a publishing house?

I’m working for two publishing houses right now: Tyche Books, which publishes The Maddie Hatter Adventures, and Dundurn Press, which will be releasing the first in The Falls Mysteries in July 2018. Between them I have a minimum of two book deadlines per year for three full years, as well as publicity/marketing/teaching obligations. So yes, at this time there’s no shortage of pressure.

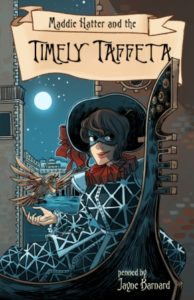

It’s not just the workload, but the creative pressure. The leisure to consider fully each individual part of each project is gone, and with it some of the joy of creation. For example, I launched Maddie’s third Adventure – MADDIE HATTER AND THE TIMELY TAFFETA – on October 23rd and was writing a video-trailer concept for The Falls Mysteries 24 hours later. It’s not my preferred way of working – I like to immerse myself in each story-world and really think about/enjoy what I’m creating – but I know it’s only for a finite amount of time, until the last 3.5 books currently contracted are written. After that, the pressure will be considerably less, and I’ll go back to enjoying myself more.

#3 Getting ready for NaNo, were you a pantser or a plotter?

#3 Getting ready for NaNo, were you a pantser or a plotter?

I was a half-pantser. Or rather, a sixth-er. I can write the first 1/6th of any story on enthusiasm alone. That’s about 50 pages into a novel, 25 for a novella, two pages (one scene) for a short story, two paragraphs for a short-short, and about two sentences in flash fiction. If I don’t have (or make) an outline at that point, my enthusiasm will die, and so will my story.

Subsequent years doing NaNo taught me an outlining method that works very well for me now, both in keeping the story going and keeping myself going. I use slips of paper on a cork board for the overall layout – to avoid muddles in the middle – and then write the entire story out in summary, just the plot points and significant bits of character development, to cement it in my head. Often during the process I’ll find spontaneous action sequences and snatches of dialogue popping up, which lend the story life beyond the page before I ever start writing ‘for real’.

Some of those spontaneous flurries from long-ago NaNo have survived years of rewrites, three changes of title, and two layers of the publisher’s in-house editing to appear on the pages of WHEN THE FLOOD FALLS when it comes out next July. Vintage NaNo-ites may recognize a single sentence near the climax that will mark which November saw me writing the bulk of that novel’s first draft.

#4 Do you still participate?

Every month is Nano for me now, or rather every season is. Although my writing goal is only 25,000 keeper words per month, there might be a third again as many written that get cut the day after I wrote them, because I’ve discovered by the writing what the essential ones are. All year round, I’m either writing or rewriting or both. Or outlining. I have to be very disciplined about social life and other distractions, which gets more difficult the more of the year one must do so.

#5 What differences do you see between writing for NaNo and writing for publishers?

Deadlines are real, not arbitrary. Publishing a book is a multi-person, multi-department coordinated effort, with each piece scheduled months or years in advance. Missing a deadline messes up a lot of people’s work life, and costs time and money to reschedule.

Crafting rather than spewing. No throwing in words and sentences just to rack up the count. Every word has to matter to the finished story, so each must be chosen with care. I write slower, but I hope I write better.

Outlines are not an option any longer; it’s simply not efficient to meander through the story and then go back to rewrite a whole lot later. With the complete outline set down before starting Paragraph #1, I can slide in as much flavour and foreshadowing as possible, directly into the opening, instead of laboriously inserting it during rewrites. I’m not a slave to the outline but knowing where I’m going frees up my creative imps to have fun getting us to the next major plot point.

Before you ask, I’m always thinking ahead into the next book or two in a series. This not only helps my character development arcs in the current book, but allows me to plant Easter Eggs along the way, tiny references or actions or gadgets that may be fun in the moment but will gain new significance when a person is re-reading or reading out of order. When the 5th and final Maddie Hatter Adventure comes out, even though each is a fully-contained story in its own right, I want readers to look back and see a complete story that runs through the five books, with consistent character development and individual character arcs and resolutions for more of the players than simply Our Heroine.

#6 What’s next up in your high-pressure publishing schedule?

MADDIE HATTER AND THE SINGAPORE STING releases in June 2018 and WHEN THE FLOOD FALLS releases in July 2018. No pressure, right?

But it’s all fun as you’ll see if you go play in Maddie’s world with her costumed friends and foes at the purely fictional Venetian Carnevale of the year 1900. TIMELY TAFFETA is available in print at Owls Nest Books in Calgary and in print and ebook formats through fine booksellers online.

Although there’s a difference between NaNoWriMo and working with publishers, NaNo is a good way to develop skills to work under pressure and to meet deadlines. As Jayne shared, there are differences in the quality of output required, but as we hone our skills and learn to work under pressure, we will achieve quality along with higher word count. Thanks for sharing your insights, Jayne! Jayne Barnard’s books can be found at Tyche Books, Amazon.com, Amazon.ca, and Kobo.

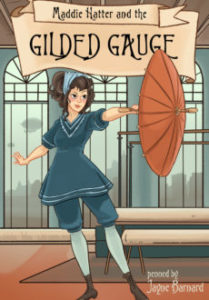

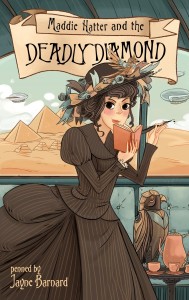

After 25 years crafting short mystery fiction, Jayne shifted to long-form crime with the Steampunk romp, MADDIE HATTER AND THE DEADLY DIAMOND (Tyche Books 2015), a finalist for the BPAA and the Prix Aurora. This book was followed by MADDIE HATTER AND THE GILDED GAUGE, a golden autumn whirl through Gilded Age New York City, and now MADDIE HATTER AND THE TIMELY TAFFETA, taking on fashion saboteurs during a Venetian Carnevale. Jayne’s contemporary suspense series, The Falls Mysteries, begins in July 2018 with WHEN THE FLOOD FALLS, the 2016 winner of the Dundurn Unhanged Arthurs. Jayne divides her year between the Alberta Rockies and the Vancouver Island shores, and her attention between writing, parasol dueling, and cats. You can visit her at her blog or on Facebook.

After 25 years crafting short mystery fiction, Jayne shifted to long-form crime with the Steampunk romp, MADDIE HATTER AND THE DEADLY DIAMOND (Tyche Books 2015), a finalist for the BPAA and the Prix Aurora. This book was followed by MADDIE HATTER AND THE GILDED GAUGE, a golden autumn whirl through Gilded Age New York City, and now MADDIE HATTER AND THE TIMELY TAFFETA, taking on fashion saboteurs during a Venetian Carnevale. Jayne’s contemporary suspense series, The Falls Mysteries, begins in July 2018 with WHEN THE FLOOD FALLS, the 2016 winner of the Dundurn Unhanged Arthurs. Jayne divides her year between the Alberta Rockies and the Vancouver Island shores, and her attention between writing, parasol dueling, and cats. You can visit her at her blog or on Facebook.