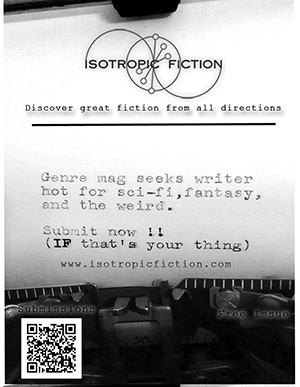

A guest post by Joseph Thompson, publisher of IF magazine.

Let’s be frank. Writers are sympathetic characters, editors are not. Writers toil in romanticized isolation but get invited to the coolest parties. They create and share every moment of joy and sorrow experienced by not just one character, but by an entire world of their creation. They brainstorm and draft, rewrite and polish, and then one day they mass submit that perfect story to the editorial altars.

Let’s be frank. Writers are sympathetic characters, editors are not. Writers toil in romanticized isolation but get invited to the coolest parties. They create and share every moment of joy and sorrow experienced by not just one character, but by an entire world of their creation. They brainstorm and draft, rewrite and polish, and then one day they mass submit that perfect story to the editorial altars.

And it gets rejected. Again. And again. And again. A few of these rejections will come with well-intended but cryptic comments like “We just didn’t feel this story had enough meat on its bones for how it had been designed,” or “Your story is like a tree with really beautiful branches but no trunk.” An extremely lucky few may come back with a request for a rewrite. The majority, however, will come with nothing but a form letter: We loved (insert story title here), but it’s not for us. Good luck placing it elsewhere.

The editors themselves don’t do much good for their public image. The ubiquitous rejection form letter is on par with a break up text message. It makes editors come across as anonymous, insensitive jerks. Now don’t get me wrong. I have nothing against editors. Some of my best friends are editors. As the publisher of Isotropic Fiction, I work closely with an editorial team whose skills I respect and admire.  As a writer, I’ve worked with a variety of editors, good and bad, from newspapers and books to literary and genre magazines. And as an editor, I’ve worked with sci-fi writers and romance novelists, journalists, and poets. There are countless essays about what editors are looking for, what their major peeves are, and how you can improve or kill your chances of getting published. Some of my favorite can be found right here on The Fictorians. After you’re done reading my essay, make it a point to check out Joshua Essoe’s “The Editing Hit List” and “Editing FAQ.” But first, I’d like to take a moment to present the contradictory image of the sympathetic magazine editor.

As a writer, I’ve worked with a variety of editors, good and bad, from newspapers and books to literary and genre magazines. And as an editor, I’ve worked with sci-fi writers and romance novelists, journalists, and poets. There are countless essays about what editors are looking for, what their major peeves are, and how you can improve or kill your chances of getting published. Some of my favorite can be found right here on The Fictorians. After you’re done reading my essay, make it a point to check out Joshua Essoe’s “The Editing Hit List” and “Editing FAQ.” But first, I’d like to take a moment to present the contradictory image of the sympathetic magazine editor.

Believe it or not, editors are a lot like writers. They smell the same, hang out at similar cafes, and many editors start off as writers. They may have gotten into editing to help pay the bills or a friend with a managerial bent may have suckered them into the job by saying “let’s start a magazine.” No matter what drew them to the editing, they continue because they want to read what you wrote. Seriously! Editors don’t just read what writers submit. They want to read it.

If you’re a writer reading this, think about the last time you asked your friend, husband, wife, or dog to read the latest draft of your story. Did you notice how their eyes darted toward the door in a desperate attempt to escape? Did they sigh? Did they take your pages only to not have read them a month later? Did they say it was nice? Editors will never treat you like that. This bears repeating: editors want to read your work. You are their raison d’être.

If you’re a writer reading this, think about the last time you asked your friend, husband, wife, or dog to read the latest draft of your story. Did you notice how their eyes darted toward the door in a desperate attempt to escape? Did they sigh? Did they take your pages only to not have read them a month later? Did they say it was nice? Editors will never treat you like that. This bears repeating: editors want to read your work. You are their raison d’être.

Editors see themselves as midwives in the creative process. When magazine editors open a file, they aren’t looking for perfection, but for some crowning creation that just needs a bit of a push. Like the midwife, the editor is there to help and guide the process, but it’s the writer who has to go through the labor. Unlike midwives who can limit the number of patients they see, editors must deal with dozens of new submissions each day.

Due to the realities of time management, editors match their efforts to the writers’. Form letters are a necessity for many submissions, and what’s written in them is true. Editors are glad to read the work even if the work is not ready for publication. And they do truly wish writers the best of luck in placing it. What the form letter doesn’t say is just as important.  When a form letter goes out, the work that came in most likely was riddled with grammatical and spelling errors, displayed a total disregard of the publication’s submission guidelines, and/or wasn’t even a complete story. The form letter allows the editor to exemplify a level of professionalism with which the writer may not have treated his or her work.

When a form letter goes out, the work that came in most likely was riddled with grammatical and spelling errors, displayed a total disregard of the publication’s submission guidelines, and/or wasn’t even a complete story. The form letter allows the editor to exemplify a level of professionalism with which the writer may not have treated his or her work.

When a work comes across the slush pile that’s well written but not quite finished, editors begin leaving comments. This is scary ground for both writers and editors. From the writers’ perspective, it can look like editors are trying to justify the rejection. Let’s face it: to a degree the writers are right. Acceptances and rejections are subjective, and the comments are an attempt to let writers know their story was looked at by an editor who gave it serious thought. There’s another side to this, however. When works are good enough to comment on, it means editors want to see that writer improve, and they want to see more by that writer.

When dealing with an endless slush pile of submissions, time is always a factor. The need for brevity frequently trumps clarity and civility, leading to the aforementioned cryptic comments. It can make editors seem gruff and unapproachable when they are actually trying to cultivate the craft of a fellow artist. And when comments include a rewrite request, writers should know that request is made in all sincerity. It means the editor wants to spend more time with the writer and the story.

When dealing with an endless slush pile of submissions, time is always a factor. The need for brevity frequently trumps clarity and civility, leading to the aforementioned cryptic comments. It can make editors seem gruff and unapproachable when they are actually trying to cultivate the craft of a fellow artist. And when comments include a rewrite request, writers should know that request is made in all sincerity. It means the editor wants to spend more time with the writer and the story.

It’s that word, “wants,” that is the key to the sympathetic editor. Regardless of their backgrounds, the majority of editors are there because they want to be. They love their work, which means they love the opportunity to see your work. Editors are very similar to writers in terms of their passion and dedication. They just don’t get invited to the cool parties.

Humbly submitted to The Fictorians editorial team.