Guest Post by Editor and Author Adria Laycraft

So you wrote a book … CONGRATS! Not as many people as you would think make it this far. Writing and completing a novel is a big accomplishment. Take a moment and relish that. You deserve it.

Now here are ten steps to take before seeking critiques from others:

1. Let it rest. The more space you can manage to put between yourself and the work, the more discerning you will be when you come back to it. But you MUST get some distance in order to see the work objectively.

2. You let it rest, right? No, overnight is not enough. Go write something else. Plant tulips. Walk the dog. Take up yoga. You’ve had your head in this story for way too long, you know it’s true, so really try and get clear of it … and only time can do that.

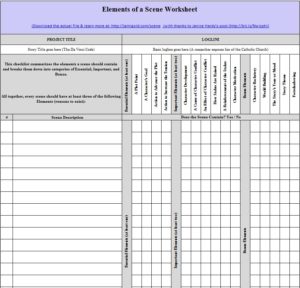

3. Now before we get into step three, I want to make sure you realize how serious I am about that rest time. If you’ve really done that, then it’s time to read through, make notes, and edit yourself. Draw up your plot points. Look for places to increase the tension. Be ruthless and delete what doesn’t further the plot, no matter how well written. You will likely do some line edits in this phase, but don’t let it consume you. There’s time enough for that later.

4. Write a back cover blurb. This tests your knowledge of theme.

5. Now write a synopsis. Two pages, single spaced, that sum up your story’s plotline, including the ending. This forces you to examine plot in big picture mode, and it will be useful later when you are sending in your submissions. Steps 4 and 5 are somewhat like reverse engineering–you want to take the finished product (your manuscript) and break it down to study the bare parts, the ingredients, and check their quality and coherency.

6. Search out your story promises. Does the opening reflect what’s important? Does the ending resolve the promises made? If your opening scene is romantic, but it turns into an action thriller, that’s not fulfilling the story promise. Does the opening hint at things that are never important later? Those story promises need to be filled, or the hints rewritten to point to important plot items. And first lines are important, so if there is a place, person, or thing featured in the first lines that isn’t an integral part of the story, it needs to be deleted.

7. Rewrite based on your findings, then scan through it again.

8. REST. Yes, again. For weeks. Months if you can stand it. Here again we benefit from seeing the story anew after we’ve ‘forgotten’ it a bit.

9. Now read again, fresh-eyed, and search for lines where you say the same thing twice and rewrite into one. Watch for where the word choices aren’t quite right and find better ones. Polish your prose so descriptions use subtext that enhance your theme, and subtle foreshadowing is in place to help make your ending surprising but inevitable. Check any spelling, punctuation, or grammar you are unsure of. You want your manuscript to appear as professional as possible.

10. You’re ready for beta readers! Remember to be clear on your theme and plot before receiving critique so you can see where suggestions work or don’t work for the story you are trying to tell. Be prepared for many more revisions! Even a book deal will mean more editing to come. Writing, and publishing, is very much a long game.

Editor, Author, and Wood Artisan, Adria Laycraft tries to use her fickle creative squirrel nature as a tool, bouncing between several projects at any given time while wondering why people stare. Her new website (coming soon!) is at www.adrialaycraft.com with information about editing services. Watch for her novel Jumpship Hope coming from Tyche Books.

Editor, Author, and Wood Artisan, Adria Laycraft tries to use her fickle creative squirrel nature as a tool, bouncing between several projects at any given time while wondering why people stare. Her new website (coming soon!) is at www.adrialaycraft.com with information about editing services. Watch for her novel Jumpship Hope coming from Tyche Books.