Gideon turned away from the scene as the blue planet’s atmosphere shredded like paper. The swelling star would soon absorb the remains of the world and the species known as man. There was no last, frantic attempt to leave Earth despite their knowledge and abilities. The whole experiment was lost. Mankind once possessed such promise.

Tag Archives: science fiction

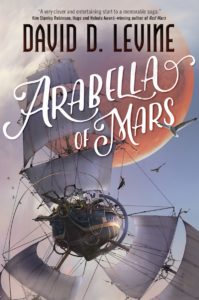

Arabella of Mars – Regency Steampunk at Its Best!

An interview with David D. Levine.

David D. Levine’s debut novel ARABELLA OF MARS is a delightful novel set in the Regency Era with a science fiction/steampunk twist. It’s an adventure filled with airship battles in the solar system, romance, drama, broken hearts and bones, automata, forests on asteroids, and settlement on a life sustaining Mars replete with its own culture. The novel’s heroine is passionate, crafty, and above all engaging. ARABELLA OF MARS left me yearning for more time in this poignant world. In this interview, I asked David about his creation of Arabella’s world.

I liked that Arabella wasn’t a man in a woman’s body. Her sensibilities and problem solving for a woman of her status respected the conventions of the time period. But she wasn’t a Mary Sue either or a Miss Marple trying to solve a problem. She was smart, deceitful, worked alongside her male counterparts, yet in her private moments we saw the personal effect of her daring choices. She feels like you wrote about someone you admire. Can you tell us who Arabella is to you.

I liked that Arabella wasn’t a man in a woman’s body. Her sensibilities and problem solving for a woman of her status respected the conventions of the time period. But she wasn’t a Mary Sue either or a Miss Marple trying to solve a problem. She was smart, deceitful, worked alongside her male counterparts, yet in her private moments we saw the personal effect of her daring choices. She feels like you wrote about someone you admire. Can you tell us who Arabella is to you.

I know a lot of writers who refer to their projects by the main character’s name — for example, “I’m working on Alfreda all this month” — but I’m usually not one of those; I usually start with the worldbuilding and come up with a character who exists in that world second (or third, after the plot). Also, the main character’s name is usually subject to change right up to the last minute. But Arabella is different. She has been Arabella from the beginning and this project, which has grown from a standalone novel to a three-book series and might grow further, has always been called Arabella. She’s someone who fights her society’s strictures and lets nothing stand in her way, but is still vulnerable and somewhat naïve. I admire her and I feel protective of her, and this is something that’s never happened to me with any of my own creations before.

Mars is a new and exotic settlement where European colonization and commerce abound. Arabella’s father is a successful business man. Arabella loves growing up on Mars and she takes great interest in this world which includes romping around with her brother, learning the culture from her Martian nanny, and taking an interest in mechanical gadgets. Despite her aptitudes, her father decides to send her home back to conventional England. Can you tell us about her father, what motivates him and why, despite his pioneering attitude, he decides to send Arabella home?

Arabella’s father is much more conventional than his daughter. Although he loves all his children, Michael is his firstborn, his heir, and his only son, and as a man of his era he is more strongly attached to Michael than to Arabella. But he does love and support her, and — as someone who left his own home planet to seek his fortune — he admires her adventurous nature more than her mother’s conservative one. When Arabella’s mother puts her foot down and demands to take the children “home” to Earth — a planet they have never even visited — he would like to keep both Michael and Arabella with him, but feels compelled to compromise. This doesn’t appear on the page, but he never really reconciled himself to this decision, and the question of whether or not he did the right thing nagged him until he died.

Your world building is persuasive, yet deft in its execution. You pay homage to early steampunk while touching upon colonization, xenophobia, but you set it the Regency Era rather than in the traditional Victorian Era. What is it about this time period that excited you?

You can blame Patrick O’Brian, whose Napoleonic War novels combine historical accuracy, adventure, and wit. I’m a great fan of those novels and when I had the idea of an interplanetary adventure in a world where the solar system is full of air it wasn’t a hard decision to set it in that period. It was a time of exploration and adventure, when the wider world was known but not well-known, and when a talented man (and why not a woman as well?) could be a warrior, a scientist, an inventor, an artist, and a diplomat all at once. Also, Mary Robinette Kowal and Naomi Novik showed that there was demand within the SF&F field for stories set in that era.

I appreciated the restraint in your approach on the issues of colonization and xenophobia – they became elements in good story telling and steampunk world building. Arabella’s reactions show, rather than simply tell, the issues. Why was it important to address these issues?

We live in interesting times, and questions of what is right and wrong when dealing with other genders, races, and cultures — and, indeed, how these distinctions are defined or if they even exist — seem more contentious now than ever before. These questions apply with equal force to history. Knowing what we know now, should we consider Columbus a hero or a villain? I felt that it would be dishonest, even immoral, to write a novel that ignored these questions… but, at the same time, it had to be a rip-roaring adventure. I hope that I’ve succeeded with both those aspects.

Tall, dark and handsome, Captain Singh, captain of the airship Diana, has a commanding and professional presence despite being the strong, silent type. Can you tell us more about him, who he represents, and what inspired his character?

Captain Singh, like Arabella, is an outsider who has nonetheless achieved a degree of success within his society — but, because of his outsider status, may see what he has achieved taken away at any time. I wanted someone Arabella could look up to and be inspired by, yet also someone who might be a little intimidating until you get to know him. He’s also someone who, because of his unique perspective, is willing to take a chance on another outsider. I knew early on that he would be Indian, to amplify the echoes of India in my version of Mars, but his background and personal history changed frequently as the book developed.

Aadim, the clockwork navigator – I can’t let end this interview without knowing your inspiration for Aadim. Despite being silent (except for the sounds he makes when he receives information to calculate navigations), he feels like a very real, yet mysterious character and he’s almost creepy because his movements feel like human reactions. When I think about it, we attribute a lot to our devices and machines. Was your treatment of Aadim in this manner a comment on our relationship with our devices or was it about the possibilities the steampunk writers saw in this world?

He is, of course, inspired by the Mechanical Turk, a chess-playing automaton of the 1700s (which was, alas, a fraud with a person inside). Originally I thought that most ships in this world would have these automaton navigators, necessitated by the difficulties of navigating in three dimensions, but as the story grew I decided to make him unique. He also provides a bond between Arabella and Captain Singh, due to their shared interest in complex automata. I had a lot of fun making his actions and reactions ambiguous, right on the edge of the Uncanny Valley. Is he completely plausible, given the technology of the early 19th century? No, not really, but this is a fictional world after all.

Thank you very much for this opportunity! I’m glad you liked the book and I hope many more people do.

Thank you for a great interview David! ARABELLA OF MARS is now a favorite! If the interview wasn’t enough to convince you to get the book, dear reader, perhaps this blurb will: Arabella Ashby is a Patrick O’Brian girl in a Jane Austen world — born and raised on Mars, she was hauled back home by her mother, where she’s stifled by England’s gravity, climate, and attitudes toward women. When she learns that her evil cousin plans to kill her brother and inherit the family fortune, she joins the crew of an interplanetary clipper ship in order to beat him to Mars. But privateers, mutiny, and insurrection stand in her way. Will she arrive in time?

David D. Levine is the author of novel ARABELLA OF MARS (Tor 2016) and over fifty SF and fantasy stories. His story “Tk’Tk’Tk” won the Hugo Award, and he has been shortlisted for awards including the Hugo, Nebula, Campbell, and Sturgeon. Stories have appeared in Asimov’s, Analog, F&SF, Tor.com, and multiple Year’s Best anthologies as well as award-winning collection Space Magic from Wheatland Press. David is a contributor to George R. R. Martin’s bestselling shared-world series Wild Cards. He is also a member of publishing cooperative Book View Cafe and of nonprofit organization Oregon Science Fiction Conventions Inc. He has narrated podcasts for Escape Pod, PodCastle, and StarShipSofa, and his video Dr. Talon’s Letter to the Editor was a finalist for the Parsec Award. In 2010 he spent two weeks at a simulated Mars base in the Utah desert. David lives in Portland, Oregon with his wife Kate Yule. His web site is www.daviddlevine.com.

David D. Levine is the author of novel ARABELLA OF MARS (Tor 2016) and over fifty SF and fantasy stories. His story “Tk’Tk’Tk” won the Hugo Award, and he has been shortlisted for awards including the Hugo, Nebula, Campbell, and Sturgeon. Stories have appeared in Asimov’s, Analog, F&SF, Tor.com, and multiple Year’s Best anthologies as well as award-winning collection Space Magic from Wheatland Press. David is a contributor to George R. R. Martin’s bestselling shared-world series Wild Cards. He is also a member of publishing cooperative Book View Cafe and of nonprofit organization Oregon Science Fiction Conventions Inc. He has narrated podcasts for Escape Pod, PodCastle, and StarShipSofa, and his video Dr. Talon’s Letter to the Editor was a finalist for the Parsec Award. In 2010 he spent two weeks at a simulated Mars base in the Utah desert. David lives in Portland, Oregon with his wife Kate Yule. His web site is www.daviddlevine.com.

The Silent Majority that is Science Fantasy

When we talk about genre-blending, we’d be remiss if we didn’t address the Mûmakil in the room (or the black hole if you prefer). After all, when we speak of “SFF” in our genre shorthand, we’re really describing two separate genres, Science Fiction and Fantasy. And the truth is that many, if not most SFF stories are actually a combination of the two.

Even a casual glance will yield many, many examples where the two genres are blended together to great effect. Though almost always referred to as one or the other, properties as diverse and popular as Star Wars (called Space Fantasy by George Lucas himself), The Dark Tower, Lost, and Doctor Who all exhibit some degree of shading between the two ostensibly separate genres.

Does your science fiction story contain technology that, while plausible, also skirts the edge of Clarke’s Third Law? Does your fantasy magic system or worldbuilding adhere to a well-established set of internal rules in the vein of Robert Jordan or Brandon Sanderson? While you can certainly cite examples of stories existing purely in one camp or the other, the reality is that Science Fiction and Fantasy are generally grouped together for good reason.

As with any literary technique, there are good and bad ways to employ this genre-blending. But rather than pretend I’m an expert on the subject, I’m going to highlight the work of a couple of lesser-known authors who have mashed Science Fiction and Fantasy to good effect*.

*Note: One of my examples is technically more a blend of Horror and Science Fiction. Now, I know Horror is its own genre, but for the purposes of showcasing a fascinating bit of worldbuilding, I’m paraphrasing Daniel Abraham and considering Paranormal Horror to be a form of Fantasy set in a malefic universe. *ducks*

For starters we have R. Scott Bakker’s The Second Apocalypse meta-series, consisting of two sub-series: the trilogy named The Prince of Nothing and the tetralogy named The Aspect-Emperor. These are grimdark epic fantasy at its grimmest and darkest (think George R.R. Martin dialed up several notches), and Bakker creates a fascinating world with a history nearly as detailed as Tolkien’s Middle Earth. His philosophy-based magic system is more powerful the more pure a sorceror’s ability to grasp the Meaning (capital “M” intended), and those sorcerous schools that have to rely upon Analogies rather than Abstratctions produce sorcery of inferior power.

But it’s the two SF elements I want to discuss. In the first, an Übermensch-like group of warrior monks have hidden themselves away for 2000 years, practicing eugenics (and terrible neurological experiments) upon themselves over all that time in order to become beings of perfect logic, utterly devoid of passion (and thus, they believe, utterly in control of their own actions in a way no other humans are). The end result is almost a separate species, so attuned to subconscious cues that they are able to essentially read the thoughts and emotions of normal humans better than the humans themselves are.

Every epic fantasy needs a Big Bad, and instead of a fallen angel-type character in the vein of Sauron, Bakker gives us the Inchoroi, an alien race whose ship (called the Ark-of-the-Skies by the inhabitants of Bakker’s world) crash-landed on his world several thousand years prior to the start of the series. Their overriding goal? They’ve been traveling from world to world in their vessel, exterminating the inhabitants of each in order to sever the living world’s connection to the Outside, Bakker’s equivalent of an afterlife. It turns out that morality in the world of The Second Apocalypse is black and white and absolute, and the actions of the Inchoroi have guaranteed their damnation by the gods after death. Only by severing the connection between the living world and the dead can that fate be avoided.

Given its uncompromising view into humanity’s ugliest sides, The Second Apocalypse can be a rough read, But given its willingness to tackle issues of free will and the self, issues that modern neuroscience (a major influence of Bakker’s) are tackling currently, there is no other epic fantasy like it.

For my Science Fiction-based example of genre-blending, I present you Peter Watts’ brilliant (and Hugo nominated) book Blindsight. It’s an alien first-contact hard-ish Science Fiction that I’m not sure will ever be topped for me. His take on truly inhuman aliens is both believable and massively unsettling (and Watts himself spent time as a research biologist), but it is his science-based vampires that I want to talk about today. In Peter Watts’ Earth, the legend of vampires sprang up from a human subspecies that went extinct thousands of years ago. While they lived, the vampires evolved to hunt humans (and thus developed significantly more strength and brain power than us) as well as the ability to hibernate for long stretches to allow time for human populations to bounce back and forget the vampires existed.

But all that brain power came with a cost. The vampires would fall into a lethal seizure at the sight of any true right angles (like, say, a cross). Right angles are not something often encountered in nature, but as soon as baseline humans began constructing habitats and cities filled with right angles, the vampires went extinct. But the lure of all that brain power proved too great to resist, so in the near-future world of Blindsight, advanced genetic engineering has been used to resurrect the vampire subspecies. One of their number is deemed the perfect leader of the expedition to investigate the alien presence that has recently arrived at the edge of our solar system.

Reading Watts’ book, you’ll find yourself half-convinced that the vampire subspecies really did exist, so convincing is his biological background work. And much like Bakker’s works, Blindsight deals with issues of consciousness and self and what those concepts even mean (if you can’t tell, these issues are a pet interest of mine).

The combination of Science Fiction and Fantasy has produced some of our most enduring works of literature and popular culture. So if you are a purist who prefers one genre to the total exclusion of the other, think again about some of the works you have read and enjoyed. You may find the line dividing the genres is a lot blurrier than you realized.

About the Author: Gregory D. Little

Gregory D. Little is the author of the Unwilling Souls, Mutagen

Deception, and the forthcoming Bell Begrudgingly Solves It series. As

a writer, you would think he could find a better way to sugarcoat the

following statement, but you’d be wrong. So, just to say it straight, he

really enjoys tricking people. As such, one of his greatest joys in life is

laughing maniacally whenever he senses a reader has reached That

Part in one of his books. Fantasy, sci-fi, horror, it doesn’t matter. They

all have That Part. You’ll know it when you get to it, promise. Or will

you? He lives in Virginia with his wife, and he is uncommonly fond of

spiders.

You can reach him at his website (www.gregorydlittle.com), his Twitter handle (@litgreg) or at his Author Page on Facebook.

Be Messy and Explore New Ideas: A Guest Post by Hamilton Perez

A guest post by Hamilton Perez.

There’s one piece of writer’s advice that is, I think, as misguided as it is persistent. The reason it does so well, of course, is because it’s not actually bad advice, it’s just often misapplied. That advice is the old adage: Write what you know.

In life, this translates to something like, “Find what you’re good at and do that.” It’s great advice for when you’re first starting out, either as a writer or in a new career; it helps you discover parts of who you are, what skills you have, unlocks your potential or at the very least points you in that direction.

Looking back, I’m pretty sure that the more seasoned writers who recommended “write what you know” were politely telling me that some part of my writing didn’t ring true. Maybe I described a place I’d never been to, or what it’s like to jump out of a plane, or travel through Europe–whatever it was, I did it wrong. I needed to go back to the beginning and start with something simpler and closer to my own experience.

I took their advice and focused on stories with more familiar settings and characters, and I immediately hit a brick wall. Should I take actual experiences and fictionalize them? Should I write about themes of friendship, love, and loss? What does that look like on page 1? The experiences I’ve had that seemed most suitable for adaptation resisted being written the most.

Trying to tell a story based on an actual experience, even with deviations and embellishments to make them properly fictional, resulted in something constraining and strangely hollow. What I learned from years focused on writing “literary fiction” (a pretentious way to say there are no dragons), was it’s not the memories of heartache or longing that most inspire me, it’s the dreams and fears of what I haven’t yet experienced. Those are the thoughts that get my heart pounding and give a pulse to the page.

For me, “Write what you know” hindered growth by encouraging me to lean on what I already knew or was already good at, instead of pushing me into unknown waters where I could really find what I’m capable of. Ultimately, what I know was just getting in the way. And I’m pretty sure I’m not alone.

Through classes, workshops, and slush reading for magazines, I’ve come across a lot of boring characters and stories surrounded by beautiful writing. And I think this “write what you know” advice is partly to blame. We have a whole generation of budding writers trying to “write what they know” by pulling from homogeneous experiences, and as a result we have literary journals full of mediocre literature. That isn’t to say there aren’t gems out there, or that literary journals aren’t a worthy pursuit, but good writing should take us to unexpected places, not simply look under the fabric of suburban life or failing relationships ad nauseam.

Eventually, I gave up on that and switched to speculative fiction. I have nothing in common (as far as I know) with pillow golems, changelings, or warrior mountain tribes of Martian sand people. But in turning to them, my writing has flourished, and has even allowed me to get back into non-genre fiction by opening up my imagination, rather than shutting it in.

Maybe writing about your past experiences does that for you, in which case, have at it. The ultimate point here is not to dump on that classic advice–it’s don’t pigeon hole your inspiration. Develop whatever interesting idea comes to you and turn it as far off the beaten trail as you can. Sure, 90% of what we create is probably garbage. Glorious garbage! But the rest might just be weird and scary enough to work. At the very least, you’ll grow.

So be messy. Explore new ideas. Go directions that feel alien to you. Poke your fingers into strange holes, ideologically speaking. In the end, you’ll find that what you know seeps through anyway, except it will do so naturally and with more honesty than if you just recounted the string of events that led to a broken heart.

They say life begins at the end of your comfort zone. I believe that’s where good writing begins as well. Because success or failure in the unknown are far more rewarding and exciting than building empires of sand along the familiar shores of home.

Hamilton Perez started writing at age twelve because there weren’t any crossovers between Terminator, Star Wars, and Jurassic Park, and he really thought there ought to be. Alas, after several cease and desist letters from everyone who read those stories, Hamilton moved on to other subjects. He is a slush reader for Fantasy Scroll Magazine and his work has appeared in Daily Science Fiction.